- The ‘Must see’ – A Winged Victory on the Capitolium

- History and Roman Legacy

- Ancient Rome Itinerary

- Fun fact – The Domus of a poet, Le Grotte di Catullo on Garda Lake

- Useful Informations for Brescia

- Our Tabernae, where to eat

The ‘Must see’ – A Winged Victory on the Capitolium

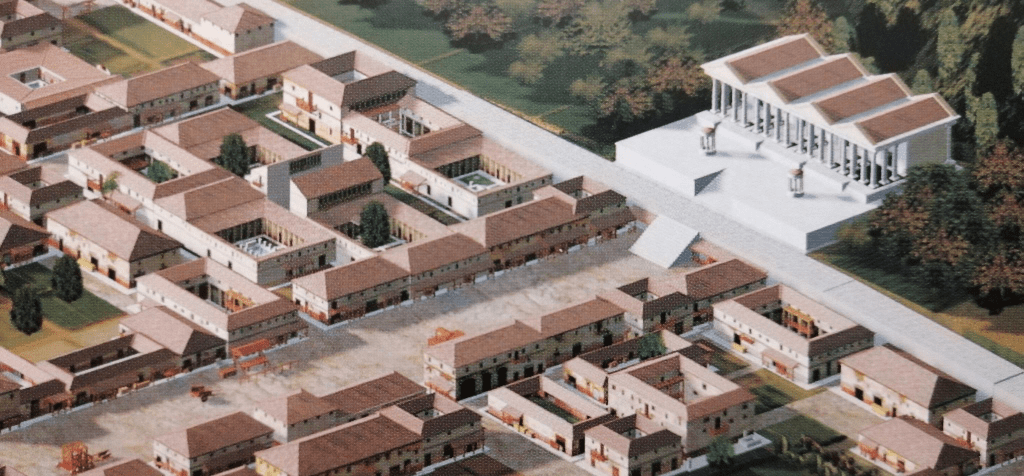

Brescia is a jewel of Eastern Lombardy nestled between lakes and valleys, in a strategic position halfway between Milan and Venice. Less famous than the near Bergamo and Mantua, it boasts the largest Roman archaeological area of northern Italy, spread over more than six hectares. A ‘little Rome’ in the heart of the city that since 2011 is a UNESCO World Heritage Site in combination with the San Salvatore – Santa Giulia monumental complex.

Rome is present in Brescia like in no other city in Northern Italy: Brixia became an ally of Rome as early as 194 BC with a treaty that recognized the Cenomani, an ancient tribe of the Cisalpine Gauls, as socii federati.

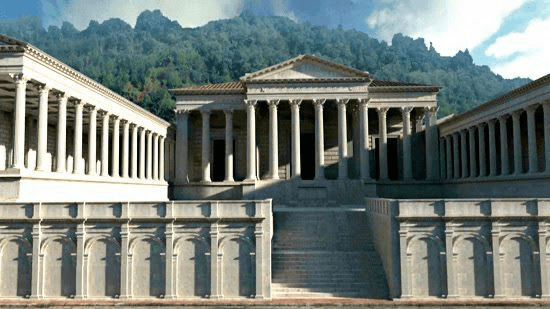

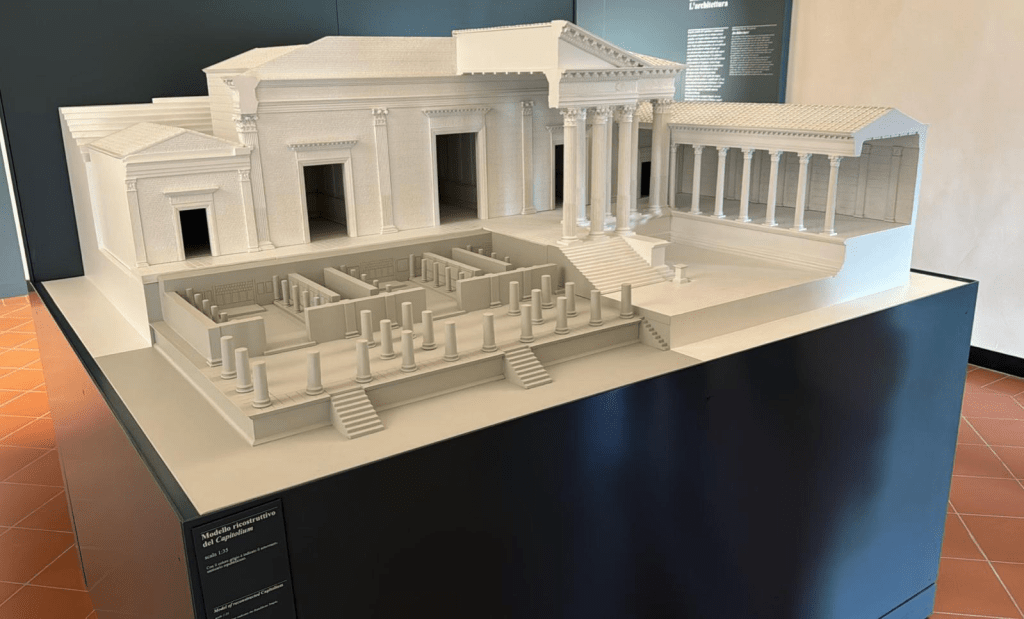

Under Augustus its inhabitants became Roman citizens and in 73 AD Emperor Vespasian built its magnificent temple, near the Roman Forum: the Capitolium, dedicated to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, the three main divinities of the Latin pantheon that were venerated in Rome at the namesake temple on the Capitoline hill. They were the guardians of the eternity of Rome and of its dominion over the world.

Worshippers gathered in the temple foreground to attend ceremonies and sacrifices.

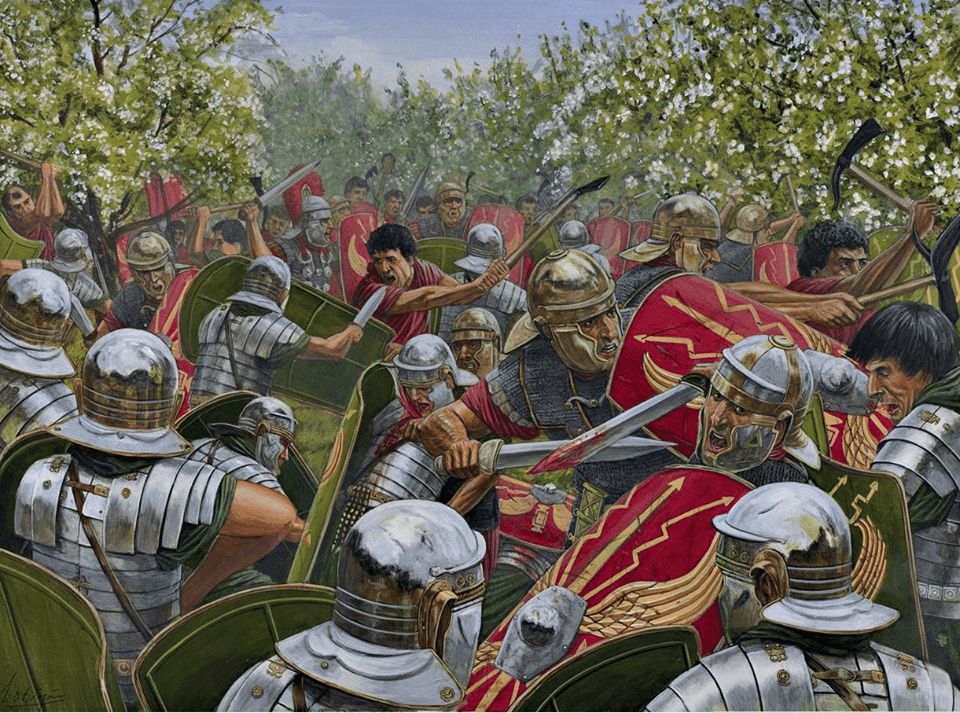

Vespasian had just defeated the army of Vitellius in the second battle of Bedriacum (Calvatone, near Cremona) that is only 60 km. away from Brixia, a city that had supported the founder of the Flavian dynasty.

It was a cruel battle: soldiers were horrified by the stench of decomposing corpses and Vitellius cheered them up with a macabre joke: “The killed enemy always smells very good, even better if he is a fellow citizen”. Vespasianus victory put an end to the bloody ‘year of the four Emperors’, 69 AD, that followed Nero’s suicide.

When Brixia was sacked by Attila the Hun, the Capitolium was badly damaged. In the Middle Ages, the temple was in disrepair and was buried by landslides and rubble falling from the Cidneo hill which preserved it for posterity until the area was excavated in 1823.

The temple was opened to the public in 2013 and it is the symbol of Roman Brescia.

The Capitolium was built on top of a temple from 1st century BC and it was located in front of the Roman Forum, the main public space in the city. The layout is that of the classic Roman capitol – the prostyle – with three main sections, or cellae, of the temple still visible and the colonnade only in the front area.

The Corinthians columns have been rebuilt to form a partial portico, on the pediment you can read the dedication to Vespasian.

Only the first one on the left, entirely white, was found intact. It was the one that emerged from the ground in the back of a small cafe in the early 19th century, when the area had not yet been investigated.

The sculpted marbles come from Botticino quarries, a few kilometres from the city. The original white parts are mixed with the pink stones added during a bold restoration from 1938 to 1945: today it would never be carried out in such an extensive and intrusive way but it offers a very clear picture of the majesty of the building.

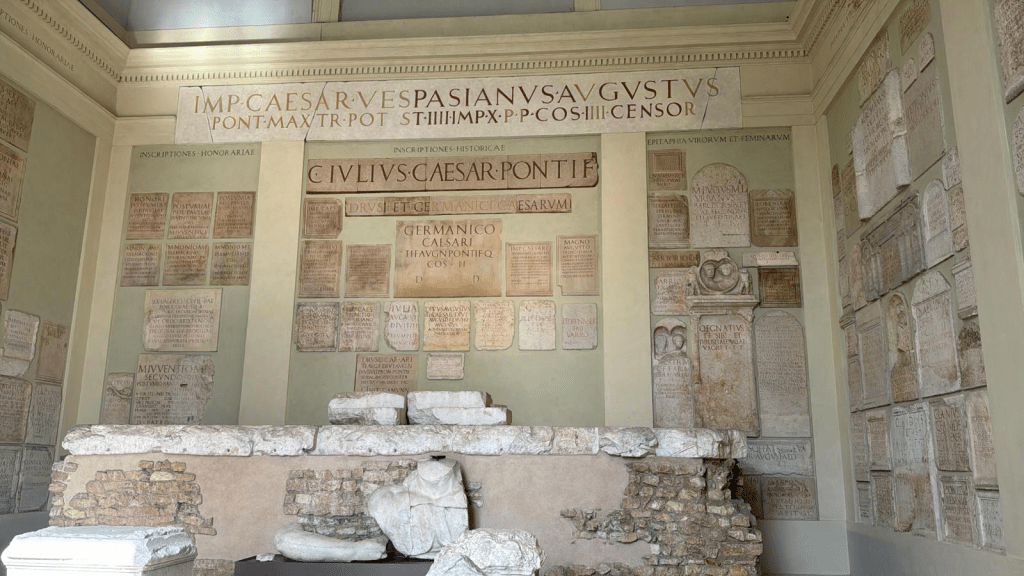

Inside, the original geometric coloured-marble pattern flooring (opus sectile) from the 1st century AD is still in place. Stone altars and fragments of cult statues and furnishings have been arranged inside the cells. On the walls of the central hall is a display of the collection of epigraphs.

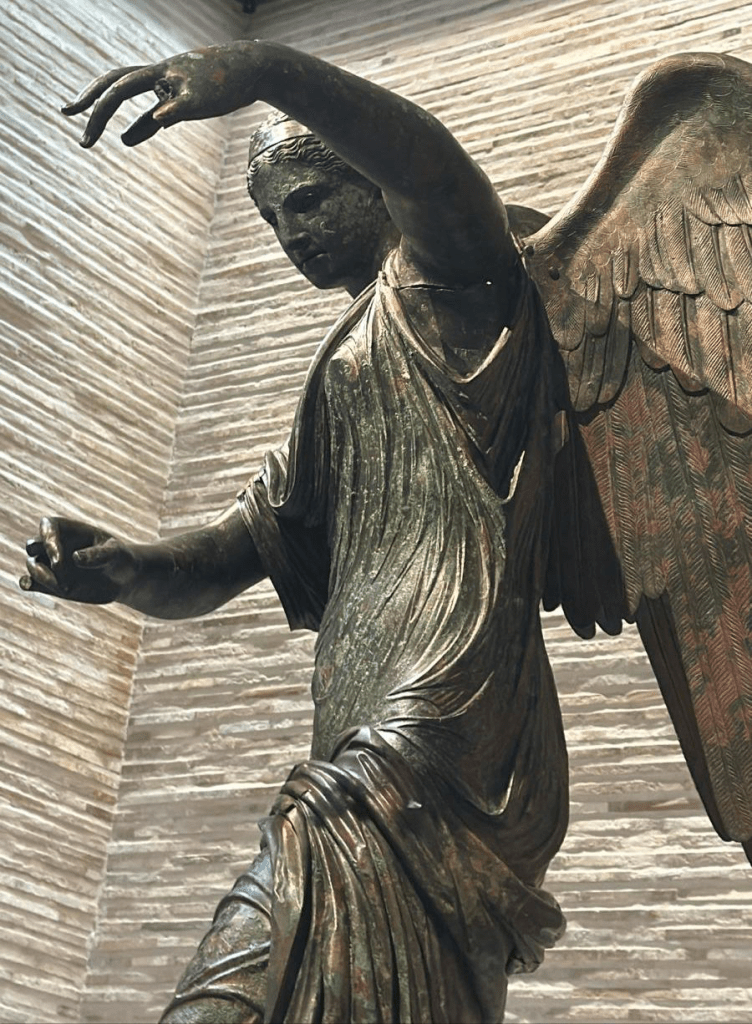

THE WINGED VICTORY – The real treasure is in the eastern cell: a marvelous Winged victory, a bronze masterpiece from the first century AD, restored in 2021 by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence. The museum setting was designed by Spanish architect Juan Navarro Baldeweg and it is conceived to make the bronze statue shine, highlighted by the monumental scenography.

The Winged Victory, possibly inspired from the famous Greek statue of Aphrodite-Venus by Lysippos, has returned to where it was found in 1826, set insidetwo walls of the ancient temple.

This statue 1.95 metres tall was discovered together with six imperial heads and hundreds of other bronze artifacts, probably hidden to avoid them being melted to be re-used for churches.

The statue is made from 30 parts that were welded together by an expert group of bronze workers, perhaps from Northern Italy. The sculptors used the lost-wax technique, by pouring molten metal into a mould made from a wax model that was melted away.

The light dress adheres closely to the body, as though it was wet. Two brooches clasped this garment at the shoulders. Silver and copper decorations are present in the band around the hair.

Victory is represented while engraving the name of the winner on a shield of the warrior god Mars that was never found. The shield was used as a mirror by the goddess in an allegory of the victory of love over war. It is possible that the statue topped the pediment of the temple, alone or next to a male figure, to celebrate Vespasian achievements. It has wings because it flies over the battlefield and it perches on the victor: a way of saying that it is not always the stronger or better armed to win.

The statue has been admired by rulers like Napoleon III (who ordered a copy before the battles against the Austro-Hungarian army in Northern Italy) and writers such as Henry James and Italian poet Giosuè Carducci (“Brescia received me… Brescia the Lioness of Italy”, he wrote in his ode to Brixia’s Victory).

History and Roman Legacy

The oldest traces of the settlement of Brescia, in Latin Brixia, from the toponymic root (brik- brig = hill) due to the Cidneo hill, date back to the end of the 4th millennium BC, in the Copper Age.

Between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC the ancient city became the most important centre of the Cenomans, thanks to its richness of water and its strategic location on the Via Gallica, the road that linked the Celtic areas north of the river Po with the Alpine valleys, the Germanic hinterland in the North with the shores of the lakes and the fertile plains of the Po to the South.

Polybius narrates that in 225 BC the Cenomans entered into an agreement with the Romans, obtaining permission to extend up to the Adda to the detriment of the Insubres to the west.

After a brief war with Romans over the colonies of Piacenza and Cremona, in 194 BC the Cenomans again made an alliance with Rome, which gave them the title of Socii Foederati.

The process of Romanization began in the 2nd century BC, with the construction of roads that connected Rome to the north, including the Via Emilia and Via Postumia.

Its inhabitants craved the ‘Roman way of life’ and new domus and temples were built by skilled workers from Southern Italy. In 89 BC, with the granting of Latin law (ius Latii), Brixia had its first urban planning, with the forum, dominated to the north by the late Republican sanctuary.

Between 49 and 42 BC, Brescia became a Municipium Romanum and between 27 and 8 BC emperor Augustus created Colonia Civica Augusta Brixia, inserted in the X Regio (Venetia et Histria).

It was one of the main cities in the North of the peninsula that Cicero called “flos Italiae“ “flower of Italy” (Philippian 3, 13). Urban planning and new public and private buildings turned it into a small Urbe: a wall was built around the hill, together with the public aqueduct.

With Vespasian’s victory at Bedriacum, near Cremona, in 69 AD, the monumental center of the city was again renovated with the construction of a Capitolium over the previous sanctuary, a wider forum and the new basilica. At the end of the century, the urban nucleus of Brixia had 10.000 inhabitants.

One century later, a theatre was built to the east of the Capitolium: it was one of the largest in the X Regio after Verona and Pola. In the same period luxurious Villae were built on the Garda lake, at Desenzano and Sirmio (See our Fun Fact, ‘The Domus of a poet, Le Grotte di Catullo on Garda Lake’).

During the imperial era Brixia grew and developed but there was still poverty among part of the rural populations. This pushed a large number of inhabitants to enlist in the legions; many were enrolled in the Legio VI Ferrata (Sixth Ironclad Legion), also known as Fidelis Constans (loyal and steadfast), that was created by Julius Ceasar using Cisalpine Gauls and fought in the Civil Wars of the 50s and 40s BC. Sent to garrison the province of Judea, it remained there for the next two centuries.

In the 4th century, Christian churches replaced pagan temples and the center of Brixia was demolished and moved from the Forum square to Piazza del Duomo, now Paolo VI (the Pope Giovanni Montini was born in Brescia), with the cathedrals of San Pietro de Dom and Santa Maria Maggiore and the baptistery of San Giovanni.

Between the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 6th century AD, the Goths settled in the city and, from 569 AD, they took over.

Ancient Rome Itinerary

The Capitolium is just one of the many Roman wonders of Brescia. You may well start your tour from this monument, illustrated in our ‘Must See’ section and then visit other gems nearby.

We advise you buy a Museum Pass or a Unesco ticket (they are valid for three days) that will allow you to visit the Archaeological area and the Museo of Santa Giulia.

The Capitolium faces Piazza del Foro, at the crossroads between the old Decumanus Maximus, the main east-west street in Roman times, and Cardo Maximus, the north-south street. This was the centre of the city’s civil, political, business, and trade life. Within the three kilometers of city walls, citizens could move and reach the Forum.

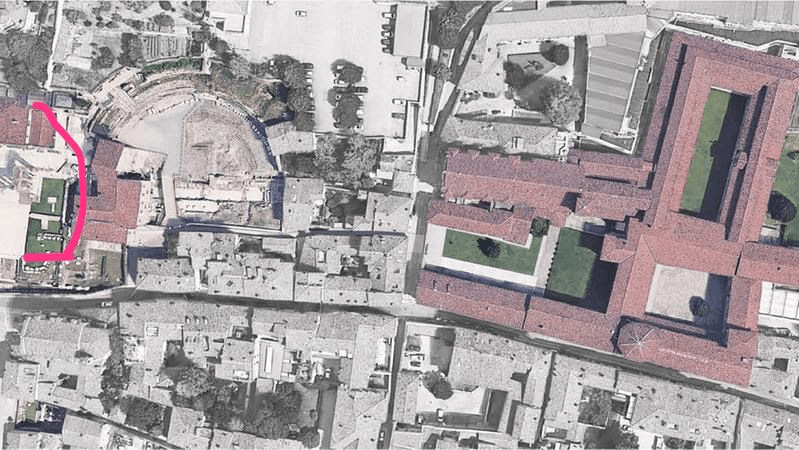

Right beneath the Capitolium, is the republican sanctuary (80 BC, at the time of general Sulla, winner of the first major civil war in Roman history) and a few steps away is the Roman Theatre (1st-3rd century AD). Opposite the theatre are the small Baroque church of San Zeno al Foro and the remains of the porches that ran around the square perimeter: the ground level at the time was much lower and these remains give a great perspective of where the city was in those old days.

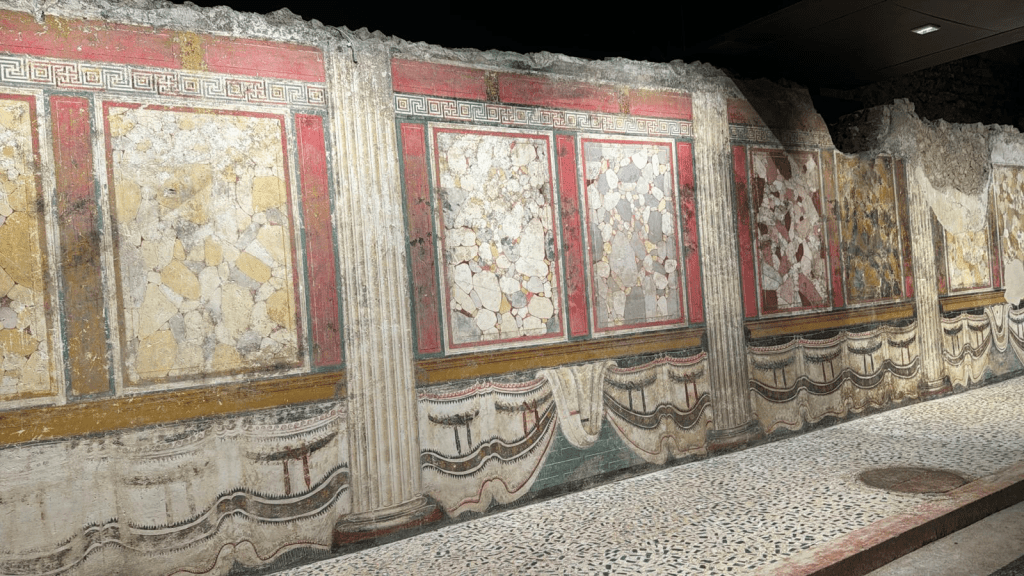

REPUBLICAN SANCTUARY

This temple, unique in northern Italy, was built by high-level workers from central Italy, who were called to erect a sanctuary in Brescia to demonstrate the city’s adherence to the cultural model of Rome, in the years immediately following the granting of Latin citizenship (89 BC).

It consists of four large rectangular halls placed side by side on a common podium, each with its own entrance and with a pronaos (portico with columns) for access, within a terrace overlooking the decumanus, today’s Via dei Musei.

The interior of each hall has beautiful and well-preserved fresco decorations.

Painted white fluted columns, corresponding to the physical columns, amplify the space; mock polychrome marble slabs are supported by a frame, below which hangs a curtain revealing the underlying masonry; the overall decorative apparatus is adherent to Hellenistic models as interpreted by Roman craftsmen.

The discovery of vaulting elements has led to the hypothesis that these aulae were covered by vaults set on a trabeation system or on architraves resting on the lateral rows of columns.

ROMAN THEATRE

Next to the Capitolium is the Roman theatre, built and extended between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD.

The cavea, the large space where spectators would sit, set on the Cidneo Hill slope, welcomes the visitors evoking the atmosphere of ancient representations. The layout of the building dates back to the Augustan age (end of the first century BC – first century AD), and was subject to enlargements and improvements over the centuries (it arrived to a capacity of 15.000 spectators), until the architectural decoration of the scene was renovated between the second and third centuries AD.

This theatre was used until late antiquity (late fourth – early fifth century AD).

Between the 11th and 12th centuries, the stage collapsed, probably due to an earthquake, and the building became an open-air quarry. In the 12th century documents tell us this space was used as a place for public hearings, but its state of abandon and the crumbling of the hill led to its progressive and definitive burial.

MUSEO DI SANTA GIULIA

The City museum (entrance in Via Musei, 81/b) has a vast Roman section with frescoes, bronzes and decorations from the public monuments in the Forum and the marvelous maximus dell’Ortaglia, with its mosaic floors and wall decorations.

The epigraphic section, set up in the large Renaissance cloister, shows an extensive and rich heritage that can be found only in very few Roman cities.

An important section is dedicated to the Late Antique period (4th-5th centuries AD), when pagan worship was abandoned in favor of Christian worship. In the area of the Capitolium, two deposits of objects and works related to the temple have been found, probably hidden in order to avoid re-use for churches.

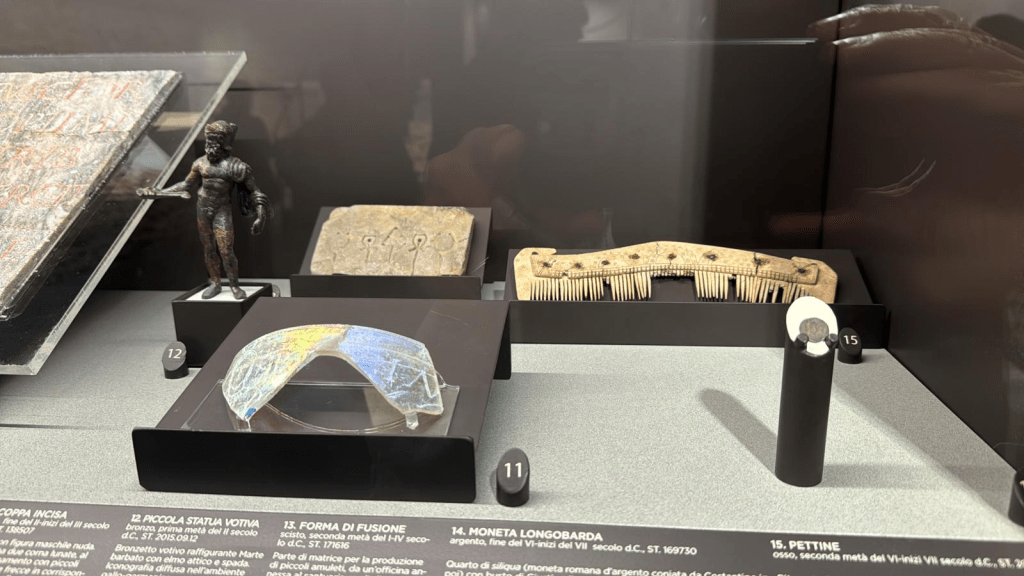

On display is a series of heads made of bronze using the technique of lost-wax casting and gilding only on the male ones, the portraits must have been inserted into stone or marble statues, as indicated by the careful finishing of the neck flaps. They were identified as members of the Flavian dynasty and emperors of the second and third centuries AD.

The other deposit, never shown in its entirety, includes a considerable amount of votive objects offered in the temple halls by worshippers; these include rare engraved glass, such as the bottle with reproductions of views of cities of the Phlegraean area, jewelry, ritual objects, including the precious knife with a deer horn handle, simple and figured oil lamps, amphorae, large plates for ritual offerings, mold-decorated ceramics, and much more.

Stone pieces show the exquisiteness of the decorations, as well as the variety of materials used. Don’t miss a corbel pertaining to the Forum of Brescia, made of local Botticino stone, that depicts the Faun, a nature deity related to the Dionysian cult, and that probably decorated one of the entrances to the Forum of Brixia.

The bronze horse breastplate (balteo) from I-II century AD belonged to an equestrian statue displayed in one of the public spaces of ancient Brixia and it depicts Roman soldiers, with helmet and armor, and barbarians, with long hair, breeches and short cape, engaged in a battle. At the center stands out the figure of the emperor on horseback.

The Statue of Silvanus, a deity linked to the world of forests and animals, is characterized by the presence of a goat-headed skin on the left side and fruits that he holds in the fold of his cloak, alluding to fertility and abundance.

There are three multimedia art installations that aim to bring visitors an immersive experience thanks to the synchronization of audio, video and light through technological devices and stage sets. Don’t miss ‘The Winged Victory. Journey of a Myth’ about the story of the statue.

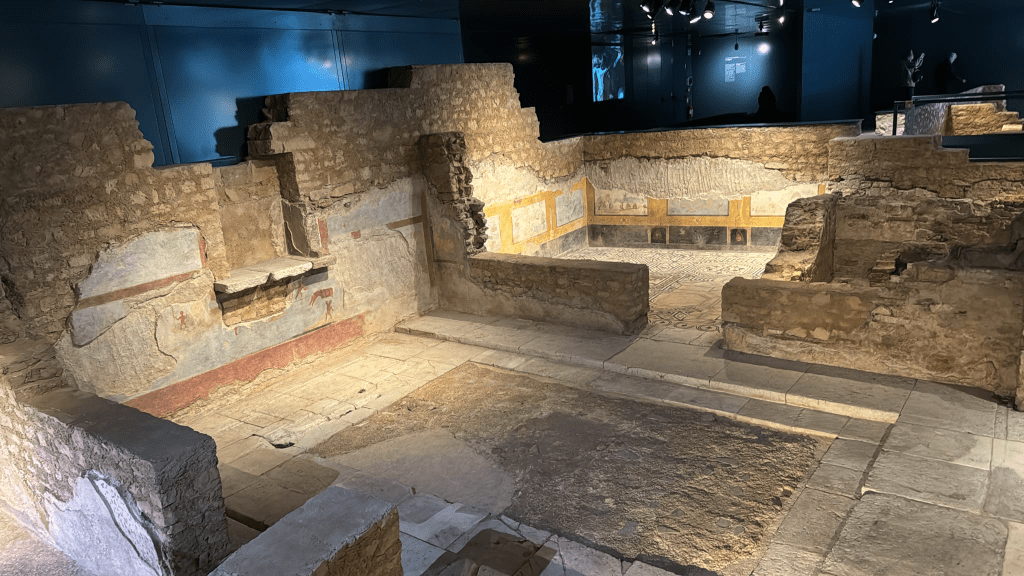

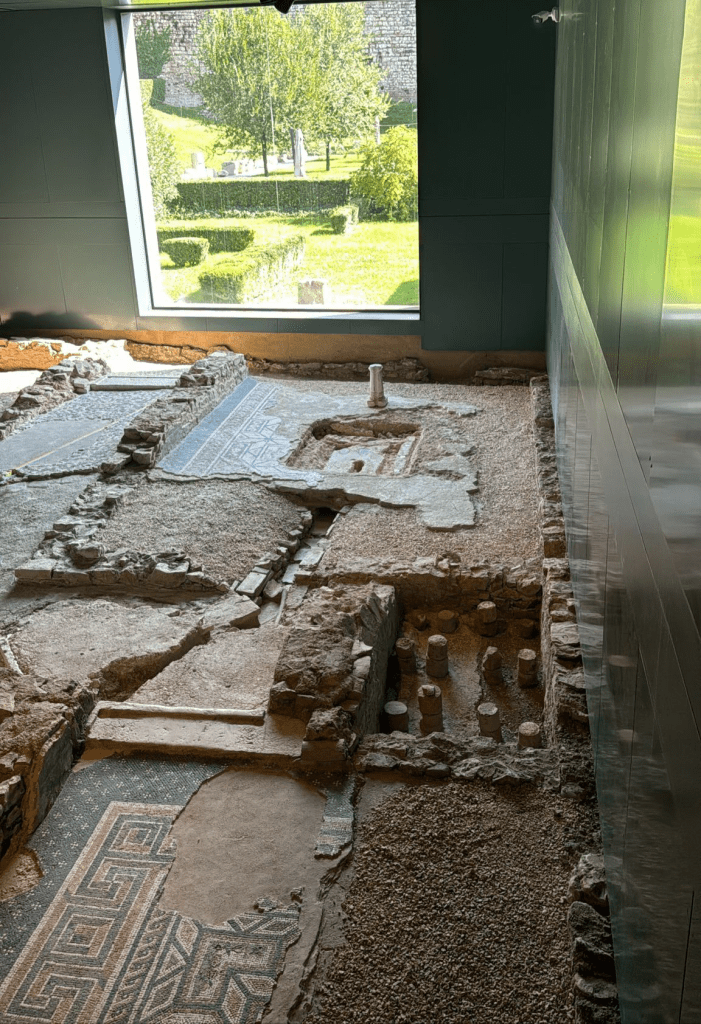

DOMUS DELL’ORTAGLIA

An exceptional archaeological treasure, among the largest in the territory of the Roman Empire north of the Po, was hidden for centuries by the vegetable gardens of the nuns of Santa Giulia, hence the name Ortaglia (Hortalia), unknowingly preserving, in the very centre of Brescia, a district of the Roman city located within the city walls, a short distance from the Capitolium and the Theatre.

An area that in ancient times had been buried by the slow landslide of the hill behind. That land, then cultivated by the nuns, covered the homes of noble and wealthy families, as can be seen from the richness of the decorations and the value of the architecture.

In the 1960s, the Museum of Natural Sciences was to be built on the Ortaglia, but the discovery of the first finds blocked the project, giving rise to the two subsequent archaeological excavations brought to light two Domus with private and representative parts, with refined mosaics, wall decorations, fountains and gardens, as well as an underground heating system.

They were part of the north-eastern Roman residential district, located on the slopes of the Cidnean Hill, between the monumental public area (the Forum square) and the eastern walls, built in Augustan age, and were inhabited between the 1st and 4th centuries AD. Between 1980 and 2002 all the rooms were excavated.

The structures are visible from a walkway suspended above the flooring of the domus and the road surface, which allows you to ‘enter’ all the rooms and reach a detached area, where some of the most significant findings from the houses are presented.

The first one you reach coming from the Museum is the Domus of Dionysus, dating back to the 2nd century.

Notable are the wall decorations and the mosaic floors with figurative scenes, including the central panel of the Triclinium floor where the young Dionysus (hence the name of the Domus) is depicted, lying on rocks with a panther.

It was built and developed between the end of the 1st century AD and the 3rd century as a courtyard house, with a central paved courtyard useful for providing light and air to all the surrounding rooms of the house. From one of the city cardi a long access corridor led from the street directly into the paved courtyard. For the owners it was a source of pride and luxury to have running water in the house.

Continuing the visit we arrive at the Domus of the fountains, which owes its name to the discovery of notable water canalization systems, which once fed the fountain.

Between the road and the courtyard there was a section of rooms that could be accessed independently from a door whose threshold can be seen with the imprints of the hinges. It is a sort of apartment clearly separated from the rest of the property intended for those who did not have the money to live in a real domus, but had enough income to afford the rent of a decent room.

From the corridor we pass to three rooms decorated in a uniform style. On a white background, yellow or red vertical and horizontal lines have been drawn, dividing the surface into a series of panels. It is the so-called linear style that spread between the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 3rd century AD.

Even though the apartment is small, there is a triclinium, a dining room. The floor has a central decorative element: a square of alternating black and white marble slabs, composed in a pinwheel. It was the central element free to view, because all the rest was occupied by the clinai, the sofas on which the Romans lay down to eat.

The floors are decorated with very bright colours, such as the representation of the four seasons, of which however only Summer has survived intact.

Raised floors are visible throughout the house which allow air to circulate to regulate the temperature of the house (hypocaustum).

Another marvel are the mosaics from San Rocchino, the remains of a rich domus discovered in 1960 in an area north of Brescia.

The peristyle domus was built as part of the reconstruction of a previous building in the second half of the 2nd century AD.

Fun fact – The Domus of a poet, Le Grotte di Catullo on Garda Lake

Gaius Valerius Catullus only lived 30 years (84-54BC) and yet he is considered one of the greatest poets of all time, for the intensity of his passions, for the fluency of his verses, for the extreme spontaneity of his feelings. He was born to a leading equestrian family of Verona, in Cisalpine Gaul, but he lived in Rome for most of his adult life.

Catullus stayed away from politics, he was delicate but also tragic and sad. “Nobis com semel occidit brevis lux nox est perpetua una dormienda”, he wrote (a brief light, for once, we have to receive, to then sleep a long and endless night).

The wealthy family’s residence in Sirmio (Sirmione in Italian) was the only place where Catullus would occasionally find some peace of mind, during his vacations from chaotic Rome. In a poem, Catullus describes his happy homecoming to the family villa at Sirmio, on the Garda lake: “Hail, lovely Sirmio, and rejoice in your master; and rejoice, you waves of the Lydia lake; laugh, you laughters echoing from my home”.

At 40 km. from Brescia, in a panoramic spot on the south of the Benacus Lake (that was its Latin name) you can visit the remains of a large Roman villa known for centuries as “grotte di Catullo”, Catullus’ caves. it is inside an archaeological park, within a vast oliveto-grove.

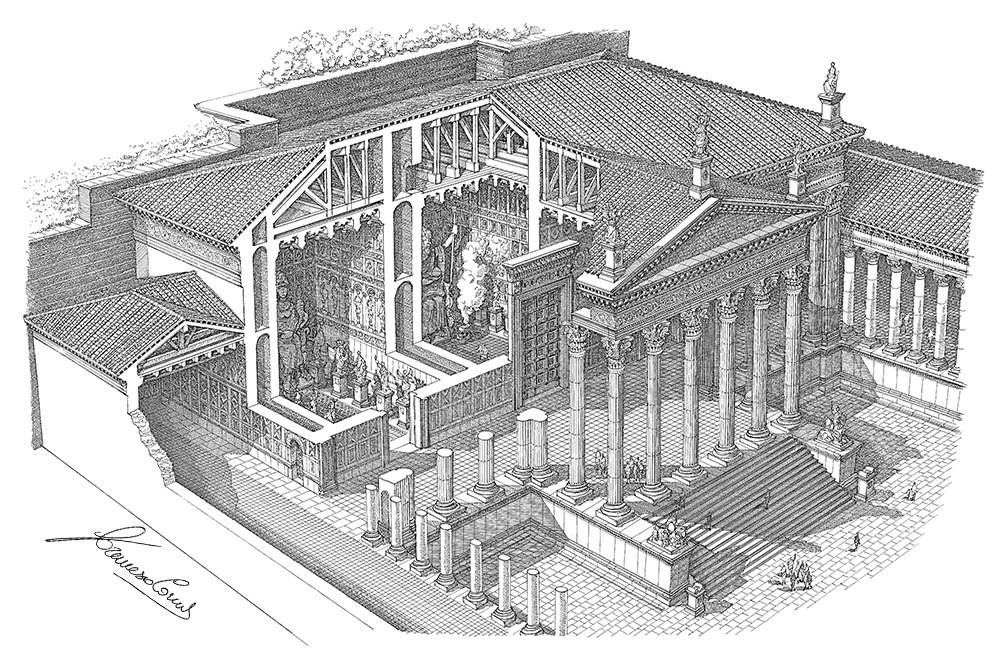

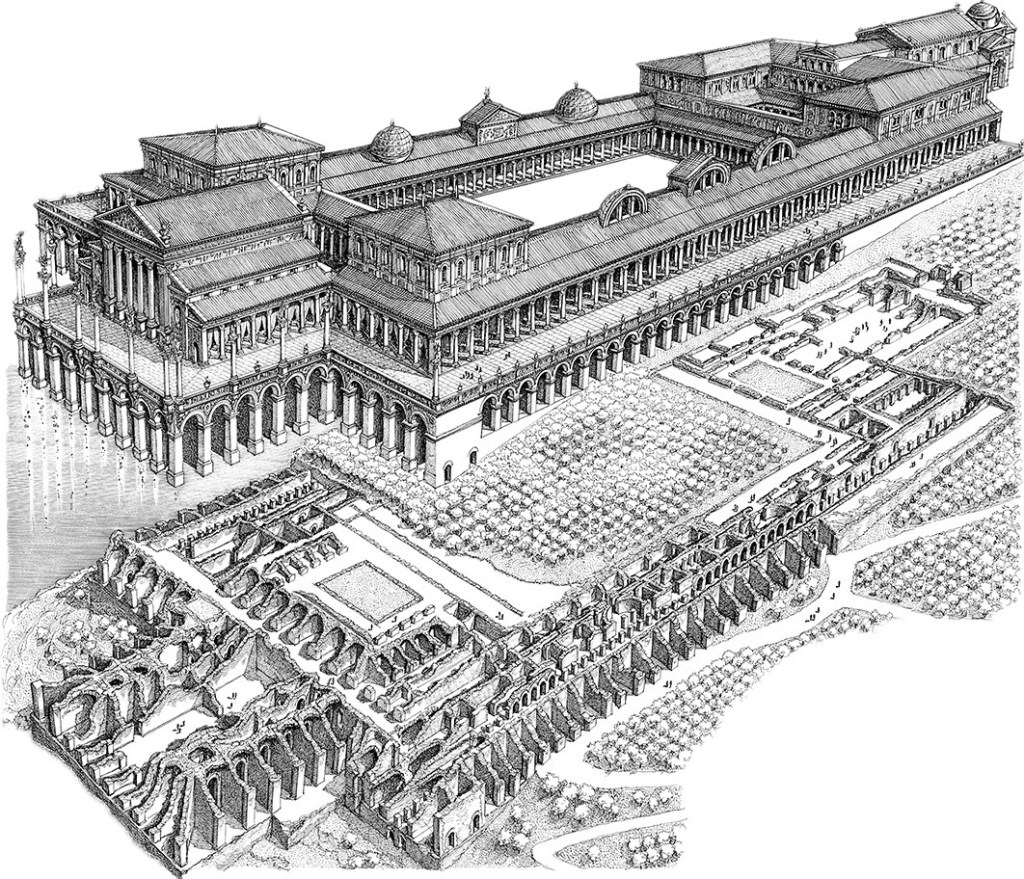

Reconstruction of the Catullus Villa (by Francesco Corni / Reproduced with the kind permission of Fondazione Francesco Corni ©)

The villa was built between the end of the 1st century b.C. and the beginning of the 1st century AD in an excellent panoramic position, at the extreme tip of Sirmio peninsula dominating the entire lake basin from the top of the rocky spur.

The name “Grotte di Catullo” dates back to the 15th century, when the rediscovery of Catullus’ lyrics associated them with the grandiose remains almost all buried and covered by vegetation. For this reason they were called ‘caves’.

Today it is considered unlikely that the villa is that of Catullus since it seems to have been built after his death. However, it is true that a structure from the Augustan era (1st century BC) lies under the one rebuilt in the 1st century AD, Catullus could well have been the owner of the older building.

The archaeological site occupies an area of about 2 hectares and is surrounded by a historic olive grove consisting of over 1500 plants. The villa was 167 meters long and 105 meters wide: it probably welcomed emperors and great political, civil and military figures traveling to the northern provinces of the Empire. It had a central part with a garden surrounded by a colonnade and two projections on the short sides: one to the south, which housed the entrance, the other to the north, with the terrace-belvedere, connected to other terraces and porticoes on the long sides. Only the large substructures remain of the northern sector, while nothing is preserved of the residential rooms, which collapsed in ancient times.

In the 2nd century BC the villa perhaps belonged to Gaius Herennius Cecilianus, quaestor of Gallia Narbonensis, member of the Roman Senate.

The Sirmione Archaeological Museum was opened inside the site in 1999 and it displays the finds collected during the excavations, along the coasts and in other settlements in the area.

ROMAN VILLA OF DESENZANO

Nearby you may visit another jewel, the Roman Villa of Desenzano that overlooked the Garda lake and had piers and docks and presumably also fish ponds for breeding fish.

It was built in several phases between the 1st century BC and the 4th century AD: what is visible today belongs largely to the last phase, when the building underwent a complete reorganization of the spaces. One of the last owners may have been Flavius Magnus Decentius, brother of the emperor Magnentius (350 – 353 AD), from which the current name of the city of Desenzano derives.

It was discovered in 1921 and you may admire, an extraordinary mosaic flooring, the thermal area and an Antiquarium with kitchen ceramics, lamps, bronze utensils.

Useful Informations for Brescia

Museo di Santa Giulia

info

+39 030 8174200 cup@bresciamusei.com

UNESCO Ticket (Santa Giulia Museum + Archaeological area)

The ticket allows entry to Brixia. Archaeological Park of Roman Brescia and to the Museum of Santa Giulia)

Full price € 15 Over 65 € 10

Summer timetable (01 June to 30 September): Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday

10:00 am – 7:00 pm

Monday (all non-holiday Mondays) Closed

Winter timetable (from 1 October to 31 May): Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday

10:00 am – 6:00 pm

Monday (all non-holiday Mondays) closed

Le Grotte di Catullo in Sirmio

Monday: h 14.00-18.00

Tuesday-Saturday: h 8.30-19.30

Sunday: h 9.00-19.30

Last admission: Tuesday-Saturday h 18.50, Sunday h 18.40

Reservation required at: https://www.midaticket.it/eventi/garda

Closing days: January 1st, May 1st and December 25th.

Because of lack of staff, the museum can be closed without notice and without discount.

Roman Villa in Desenzano

via Crocifisso, 22 – Desenzano del Garda

Open daily 9:00 – 18:00

Tuesday to Sunday (1 March – 31 October): 8.30-19

Tuesday to Sunday (1 November – 28 February): 8.30-16.30 archaeological area, 8.30-19 antiquarium

Closed: Monday unless public holiday, otherwise closed Tue. Other closures: 25 Dec, 1 Jan, 1 May

Tickets: full €4; reduced €2; free under 18 and first Sunday of the month.

Our Tabernae, where to eat

I Du dela Contrada – Contrada del Carmine, 18/B Brescia (traditional Brescia cuisine)

Leave a comment