- The Must See – The Roman Theatre

- History and Roman legacy

- Ancient Rome Itinerary

- Fun Fact – Roman Theatre, a Feast for All

- Useful Informations

- Our Tabernae – Where to Eat

The Must See – The Roman Theatre

What do the Caudine Forks, a Pyrrhic victory and a theatre and arch among the finest of the Roman Empire have in common? They are all part of the Roman legacy of Beneventum, a Samnite and then Roman city in the Apennine hinterland of Campania, in the southern part of the Sannio region. The city has witnessed some of the most important chapters of Roman history in Southern Italy: located between the Sabato and Calore rivers, in a valley surrounded by hills, it was along the most important consular road in Southern Italy, the Appian Way, the so-called ‘Queen of Roads’.

Originally called Maleventum, Romans changed its name to Beneventum (literally good, fair wind) when they conquered it in the third century BC. They believed that “Male” (evil) was an ill omen and so they modified it to include “Bene” (good).

Industrial partner: http://www.maregroup.it

Academic partner: https://www.urbaneco.unina.it/. Project Manager: ing. Giuseppe Di Gioia – https://www.linkedin.com/in/inggiuseppedigioia/(DGT progetti)

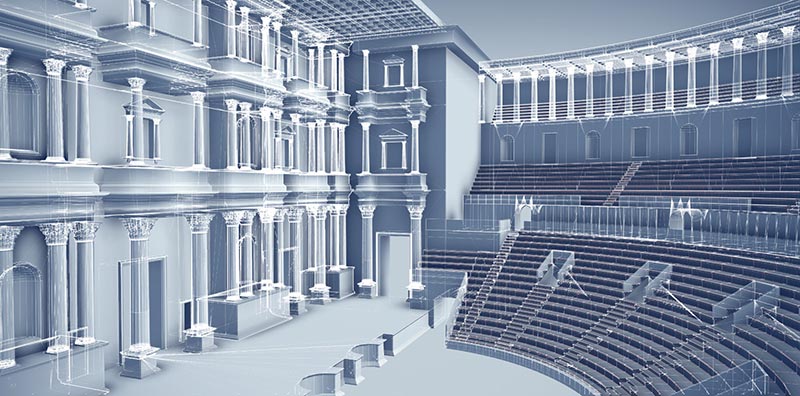

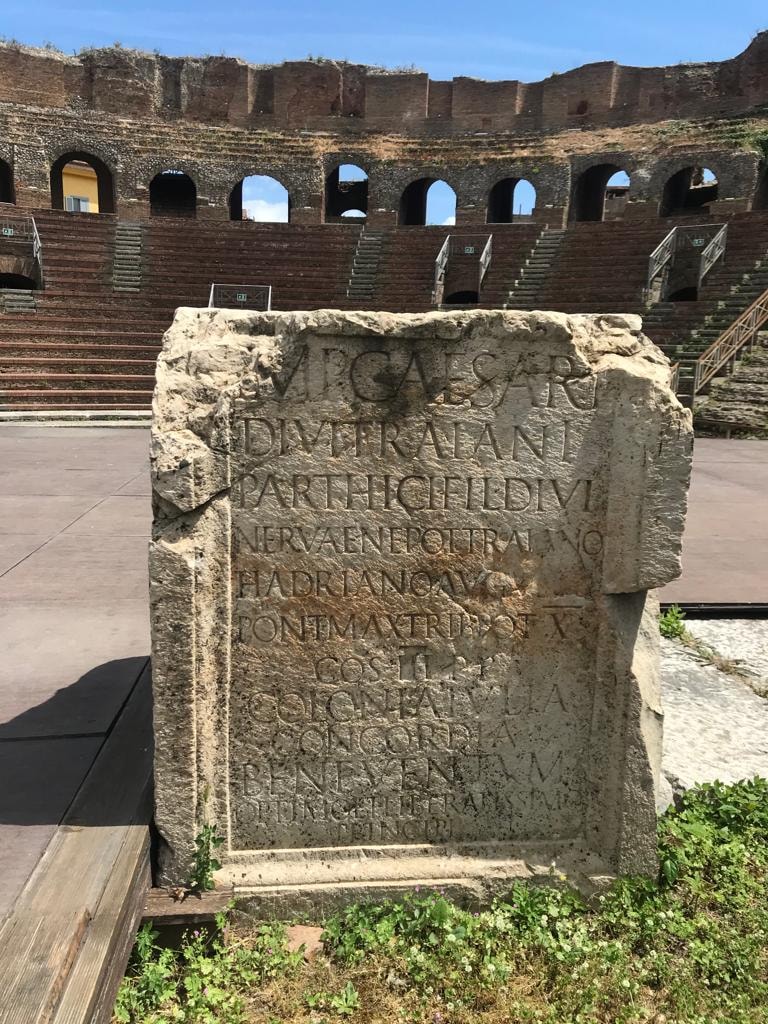

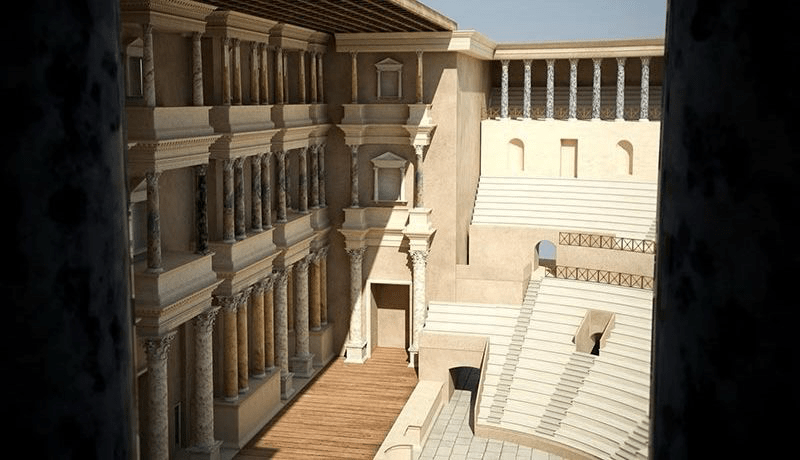

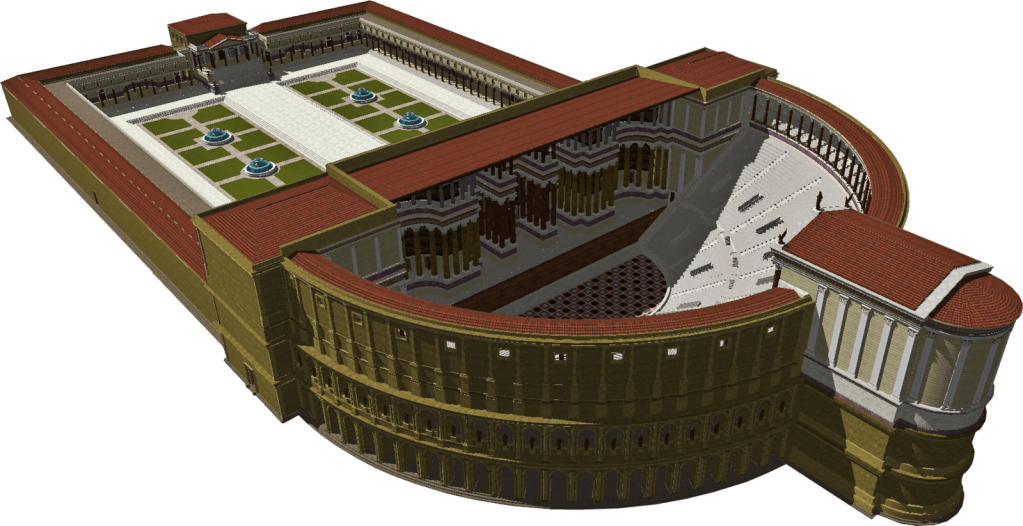

The Roman theatre of Benevento was built in the 2nd century AD under emperor Trajan and inaugurated under emperor Hadrian in 126 AD. Recent excavations show that the theatre was built on the remains of a previous building, probably destroyed by a flood at the beginning of the 1st century AD.

It was subsequently enlarged by Caracalla between 200 and 210 AD.

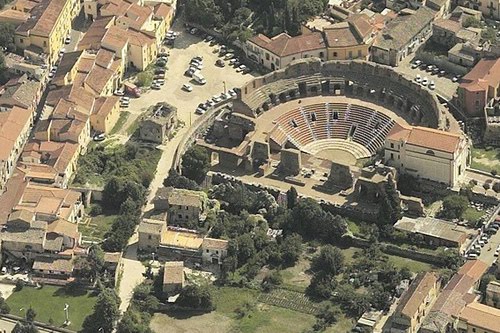

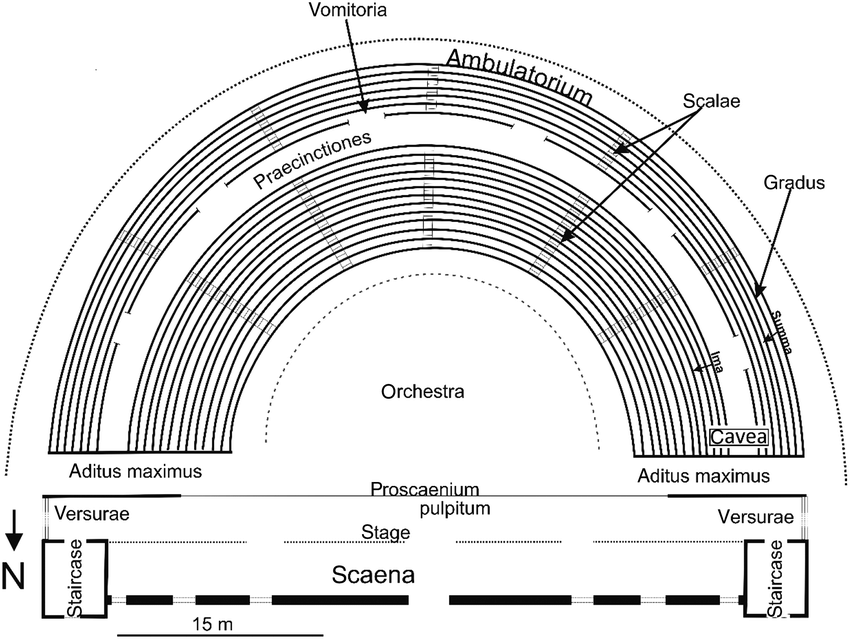

It is one of the most important and best preserved spectacle buildings in Italy. It was built in the western part of the ancient city, between today’s Pont’Arsa and the Duomo, near the cardo maximus. Its shape is semicircular and it is very huge: with 90 meters in diameter it could accommodate up to 15,000 spectators.

Built in opus caementicium (cement work) with facings in blocks of limestone and brick, it was originally made up of 25 arches in three orders, of which only the first and a small part of the second order are preserved today.

It is a majestic place that still today, after almost two millennia, preserves its original civic role as the cultural heart of the city.

The cavea was divided into two sectors and surmounted by a gallery, whose internal wall was decorated with niches: the function of this gallery was to entertain the public during the breaks in the shows, allowing them to walk around and to exchange a few words while admiring the statues in the niches.

The cavea had a semicircular plan and three orders: Tuscan, Ionic and Corinthian, of which only the lower order is preserved, 25 arches on pillars with Tuscan (similar to the Doric order except that they are not fluted) semi-columns.

The arches of the cavea contained male busts in the lower order and probably masks in the higher orders. Some of these masks were reused in buildings in the city’s historic centre. On the scene, in correspondence with three monumental doors, there were semicircular niches in which statues were placed. In the rear area of the scene, the structures of three stairways are still visible.

The steps were covered with marble slabs, which not only made the building much more sumptuous, but also had an acoustically reflective effect, as it has been proven by the sound analysis that highlighted the spectacular reverberating effect of the theatre.

At the base of the steps there is a semicircular space, the orchestra. In the Greek theatre it was intended for the chorus and the dances, while in the Roman one it was reserved for important spectators, or, as is the case in Benevento, a simple space of disengagement that separates the audience from the stage.

A study on a model of Benevento theatre has revealed its excellent acoustics, typical of Greek and Roman theatres. The secret was a perfect knowledge of the reverberation of sound waves on wood and stone, and the position of these materials with respect to the sound source. The arrangement of the steps also plays an important role in the good diffusion of sound like the seats positioned at a constant distance that contribute to an excellent propagation of the audio. The acoustics are more suited to prose than to musical or opera performances.

Behind the stage there is an architectural structure called frons scenae, a sumptuous and highly decorated backdrop that was meant to represent a neutral background for every type of performance. The setting could sometimes be suggested by the addition of painted panels.

The pulpitum of the theatre in Benevento had a marble decoration at the base that clearly separated it from the orchestra with a visible and highly decorative break.

The actors entered on stage from two lateral wings, called versurae: these were two rooms where they prepared themselves, wearing costumes and masks, and from which they could directly access the stage.

In the Benevento theatre the versurae had mosaic floor decorations and the walls were adorned with polychrome marbles. The same marbles must have also adorned a large part of the theatre, with a sumptuous colored effect.

The public access to the theatre, instead, was via an avenue, decorated with marble theatrical masks, which reproduced, in bigger dimensions, the masks that were used by actors on stage: these were a tool with a dual utility, first of all they allowed to capture a fixed and invariable expression even to those who sat far from the stage, to whom the facial features of the actor would certainly have escaped (sometimes the distance of the furthest rows reached even 20m and more).

In fact to make the character more alive, the actor used a lot of body movement, also to counterbalance the expressive fixity of the mask; on the other hand the large mouth opening in the mask amplified the vocal emission.

In the area surrounding the theatre, archaeological excavations have brought to light an area most likely used as a dance and theatre school, to bring together actors’ associations and as a factory for musical instruments and stage machinery.

It is not clear when the monument lost its function as a theatre: what we know is that it remained outside the walls built in the fourth century AD, which testifies the narrowing of the perimeter of Beneventum in the late antiquity period.

In the Middle Ages the monumental complex was invaded by private dwellings and stripped of the stone elements, to be reused in other buildings.

The “fragmentation” and the presence of houses is documented in paintings and images of the 18th and 19th centuries.

The church of Santa Maria della Verità was erected on the ancient lamioni (base) of the theatre in 1782, at the behest of Cardinal Francesco Maria Banditi (1706 – 1796), archbishop of Benevento.

The “rediscovery” of the theatre began at the end of the 19th century (1890) by architect Almerico Meomartini (1850 – 1923), who carried out the first excavation works at his own expense.

The post-war reconstruction, aimed at safeguarding the cultural heritage of the city, made the theatre area a deposit of statues, stone elements and epigraphs from the damaged buildings. In the 1950s the restored theatre was returned to the city and its original function as a venue for performances.

History and Roman legacy

According to a legend, Beneventum was founded by the Greek hero Diomedes, who landed in Italy after the destruction of Troy. He would have donated to the city the tusks of the mythical Calydon boar killed by his uncle Meleager. The boar is still the symbol of the city even though it is very unlikely that Benevento was founded by Greeks.

A coin of the 4th century BC seems to indicate that the city was called Malies, which led to the name of Maloenton, Greek name meaning herd of sheep or goats, a reference to this important activity by the Samnites.

However, the founders of the first settlement were probably the Osque people (Osci or Opsci in Latin) before the the arrival of the Samnites .

In 314 BC, the name of Maleventum appeared in the first Samnite war waged by Romans against the tribes of the Sannio region led by the Hirpins. This war ended with the conquest of Latium by the Romans.

During the second Samnite war from 327 to 304 BC, the Romans suffered a severe defeat, with their humiliation in 321 BC at the Caudine Forks, located at 34 km east of Maleventum, between Arpaia and Montesarchio. The Roman forces were ambushed on the Apennine, in a narrow valley flanked by steep mountains.

The Samnites, under the command of Gaius Pontius, blocked both entrances to the valley and trapped the Roman legions. Pontius imposed that the Roman soldiers were to pass under a yoke formed by crossed spears, a symbol of total submission and dishonor for an army.

Subsequently, the Samnites convinced other peoples of the center and south of the peninsula (especially Etruscans) to rise up but from 298 to 290 BC the Romans defeated each of the Samnite allies and imposed them a treaty in 290 BC. Maleventum was occupied by the Romans and in 275 BC it was the scene of the victory against the king of Epirus Pyrrhus and his allies (Greeks, Tarentains and Samnites).

In 268 BC the Roman colony was renamed Beneventum, its old name being associated with bad luck.

The area was the scene of battles during the Second Punic War against Carthage, which saw the defeat of the Carthaginian general Hannon in 214 and 210 BC.

The original castrum (fortress) had a perimeter of about 2100 meters and a pentagonal layout that enclosed an area of almost 30 hectares, organized on the basis of 35-meter wide blocks.

Benevento became a Roman municipality in 86 BC and at that time it was described as one of the most prosperous cities of the south of the peninsula.

Its growth continued under the empire, with the construction of Via Traiana, a variant of the Appian Way from Benevento.

In the 4th century AD it was the most populous city of the south after Capua.

Beneventum suffered a terrible earthquake in 369, and it declined at the same time as the Roman Empire.

In 410, the Visigoths seized it, then the Vandals arrived in 455. When the Western Roman Empire collapsed, the Goths conquered the city in 490. In 545 AD Benevento was ravaged by Totila, King of the Ostrogoths.

Ancient Rome Itinerary

Trajan’s Arch is the symbol of Benevento along with the Roman theatre. Your tour can start from here, in the square surrounded by the circular Via Traiano.

Also called Porta aurea (golden door), it was built in 114 AD to celebrate the inauguration of the Via Traianea, a “shortcut” to the Appian Way which connected Rome to the southern provinces, to Brindisi and therefore to the East.

At that time the city was consolidating its strategic and political role while the Roman Empire was reaching its greatest expansion. The arch was a testimony to the last great conquests of the Roman Empire, from Dacia to Germany up to Mesopotamia.

The arch, one of the best preserved in the world among those with sculptural reliefs, is built with blocks of limestone covered with Parian marble (from the Greek island of Paros in the Aegean Sea) and it is 15.60 meters high and 8.60 meters wide.

Walking around it you can ‘read’ it as if it were a historical comic book. It narrates the conquests and achievements of Trajan at war and in the administration of the Empire.

Each facade is framed by four semi-columns, arranged at the corners of the pylons, which support a protruding entablature, beyond which stands a large attic with a dedicatory epigraph.

The Latin inscription presents the same text on both sides. Trajan is remembered as “Optimus“, an enlightened prince that Dante himself placed in Paradise as evidence of his undisputed greatness.

In the plumes of the arch of the fornix there are personifications of the Danube and Mesopotamia on the external side and of Victory and military Loyalty on the internal side. Along them are the geniuses of the four seasons; on the keys of the arch other personifications are depicted (Fortuna, on the external side, and Rome on the internal side).

The internal sides of the fornix present two other large sculpted panels, depicting scenes of Trajan’s activities in the city of Benevento: on the left, leaving the city, the Sacrifice at the ceremony for the opening of the Via Traiana (Trajan can be seen among the lictors during the ceremony); on the right the institution of alimenta (symbolized by the loaves on the table in the centre) in the presence of lictors, personifications of Italic cities and Italians with children in their hands and on their shoulders. On the vault, decorated with coffers, a depiction of the emperor crowned by a Victory appears in the centre.

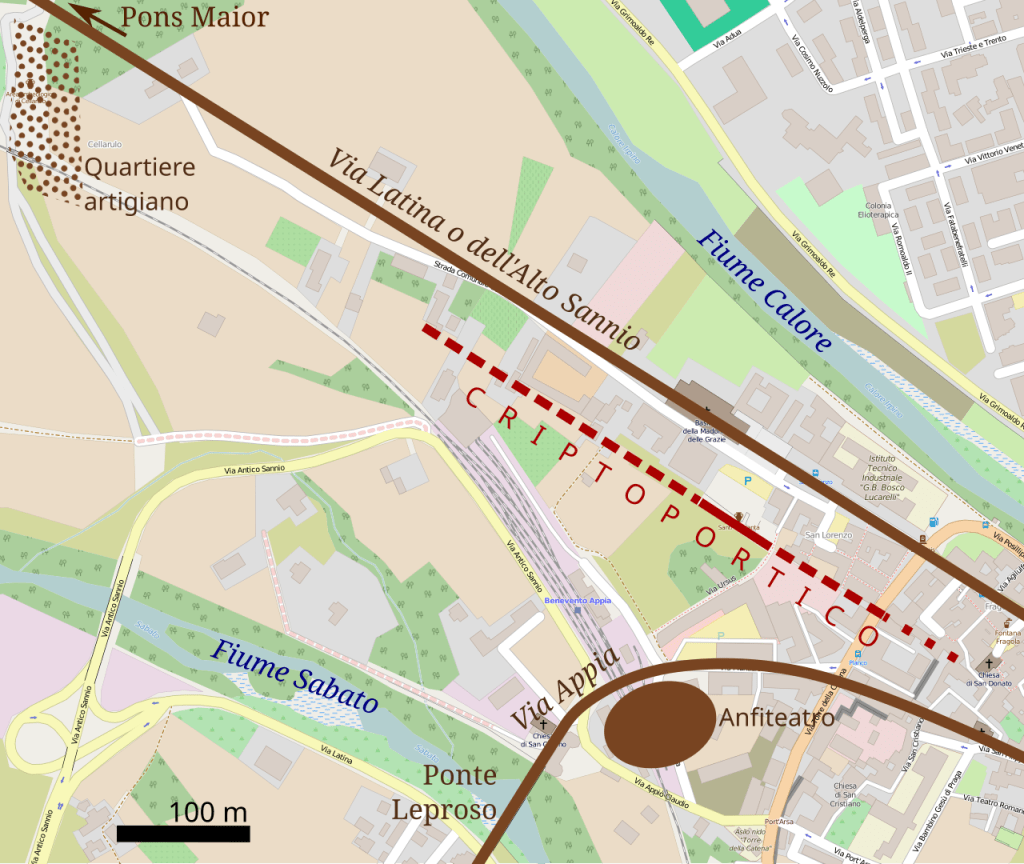

THE CRYPTOPORTICUS OF SANTI QUARANTA

The Santi Quaranta are the remains of a long cryptoporticus from the Roman era located in the alleys near Viale San Lorenzo. A cryptoporticus is a covered corridor, a semi-subterranean gallery with vaults supporting a porticus above ground.

Built in the 1st Century AD, it derived its name from a church dedicated to the forty Christian martyrs of Sebaste (today’s Sivaslı in the Uşak province of Turkey) that was built on top of it. The Santi Quaranta are military martyrs killed in 320 AD under Licinius, when the emperor, out of hatred for his colleague Constantine, resumed the persecution of Christians. The church has been destroyed but it still gives its name to the complex.

The building consisted of a system of vaulted galleries and it was probably a monumental construction within the area of the Forum.

In ancient times it had a façade with offsets and ten windows, 3 of them artificial. It was damaged by several earthquakes and by the bombings of 1943.

THE ARCH OF THE SACRAMENT

The Arch of the Sacrament, on Via Carlo Torre at the corner with Palazzo Arcivescovile, was built betwen the end of the 1st century AD and the beginning of the 2nd. It was the entrance to the Forum area for those coming from the Theatre district.

The arch is supported by two pillars in opus latericium resting on stylobates in opus quadratum. The diameter of the arch is approximately 5 meters and it is surmounted by a brick discharging arch. It is currently almost completely devoid of marble covering and the statues that were in the niches of the two main facades are missing.

The triumphal arch was completed with an upper crowning between 1633 and 1635 during a restoration commissioned by Archbishop Agostino Oregio.

During restoration and redevelopment works in the area, the spa complex also emerged which, since 2009, has become part of an urban archaeological route. The area develops behind the city cathedral.

THE AMPHITHEATRE

The remains of the Roman amphitheatre were discovered in 1985 between via Munazio Planco and the Leproso bridge. Historical sources suggest that it existed in the year 63 AD, because Nero attended a gladiatorial show in the city.

Vatinius, a former cobbler from Benevento who had gained a prominent position in the imperial court, organized a gladiatorial show in the city in honor of the emperor. In Benevento it is widely attested that munera gladiatoria were practised regularly and the city was a detached seat of the Ludus Magnus, the most important gladiator school.

The amphitheatre must have been very large: the two axes of its elliptical plan are thought to have measured 160 m and 130 m respectively with a height of about 25 m. Some elevated portions of the first level of the cavea are still visible. The perimeter wall with two buttresses is distinguishable and sections of the radial walls are preserved (eight sectors of the outermost cycle and two of the innermost cycle).

Part of the building is buried under the Benevento-Cancello railway tracks.

THE LEPROSO BRIDGE

The Leproso bridge, with the typical humpback structure, allowed the Appian Way to cross the Sabato river, about 1 km south-west of Benevento. The name is probably a transformation of Ponte Lebbroso since a lazzaretto (hospital for lepers) may have been near it in the Middle Ages. The ancient name of the bridge was Ponte Marmoreo (Lapideo in the documents), as it was covered in travertine.

The bridge was destructed by Goths and today only one of the pillars remains of the original structure, built in opus quadratum (square work).

Fun Fact – Roman Theatre, a Feast for All

For a Roman citizen, going to the theatre in the morning to watch a show was a festive experience. Admission was free for everyone – citizens and slaves, men and women, old and children – but a sort of ticket was needed, usually a bone tablet, to check the number of spectators and give them assigned seats.

In the Republican period performances took place inside temporary wooden theatre buildings because the rigid Roman morality considered them a form of entertainment that led citizens to idleness.

Only in 55 BC the first stone theatre building was erected in Rome, in Campo Marzio, under consul Pompey. To get around the rules, he erected a temple to Venus Victorious and in front he created a large semicircular access staircase with multiple levels: the steps of the future theatre.

The sacred function of the temple made the theatre legitimate. Soon afterwards the stage arose that would entertain 20,000 spectators. A large portico at the back of the stage was finally built as a Curia for Senate meetings. This is the famous “Curia Pompeia” where on March 15, 44 BC, Julius Caesar was killed. Much blood bathed that statue (of Pompey) so much so that it seemed that Pompey was avenging his enemy”, wrote Plutarch.

The earliest Latin plays to have survived intact are the comedies of Plautus (active 205–184 B.C.), which were mainly adaptations of Greek ones. Latin tragedy also flourished during the second century BC (Seneca was the greatest author): it was inspired by Greek mythology or by famous episodes from Roman history. In the Imperial age the popular forms of theatrical entertainment were mime (ribald comic productions with sensational plots and sexual innuendo) and pantomime (performances by solo dancers representing mythological themes without voice, supported by instrumental music and a chorus).

The main occasions for dramatic spectacles in the Roman world were yearly religious festivals, or ludi, organized by elected magistrates and funded by the state treasury. Temple dedications, military triumphs, and aristocratic funerals also provided opportunities for scenic performances.

Despite the enormous capacity of theatres, the distribution of seats was based on rigid rules that assigned a sector of the theatre to each social class. The comfortable seats in the front rows, sometimes real marble benches covered with cushions, were reserved for the senators; a little higher were the rows of the knights. The last rows of the steps went to the population; finally at the top, higher and further from the scene, were the women with children and slaves.

Theatre for Romans could be emotional like at a fabula cothurnata (Latin tragedy with a Greek themes adapted for the Roman public, named after the cothurno , the shoe worn by the actors) or a moment of excitement for a fabula praetexta (Latin-themed tragedy about myths and legends regarding the history of Rome whose name is due to the purple-edged toga praetexta worn by senators and prominent figures). Or else it could be a moment of laughter for a fabula palliata (Latin comedy with a Greek theme, which took its name from the pallium, the typical cloak worn over the tunic) or a fabula togata (a comedy set in a Roman environment and which took its name from the toga, the characteristic Roman garment).

Useful Informations

Roman Theatre Piazza Ponzio Telesino

Admission 5,00 €(2€ with reduction)

drm-cam.teatrobenevento@cultura.gov.it

+39 0824 47213

Open Every day from 9 am to 5:30 pm.(7,20pm in summer)

Our Tabernae – Where to Eat

Locanda Scialapopolo – Via Francesco Paga, 69 (Fish, Mediterranean). +39 331 7920783

Gino e Pina – Viale dell’Università, 93 (typical Benevento cuisine). +39082424947

info@ginoepina.it

Leave a comment