- The ‘Must see’ – San Lorenzo columns

- History and Roman Legacy

- Ancient Rome Itinerary

- Fun Fact – Milan Forum and Augustus’ rage

- Useful informations for Milan

- Our tabernae, where to eat

The ‘Must see’ – San Lorenzo columns

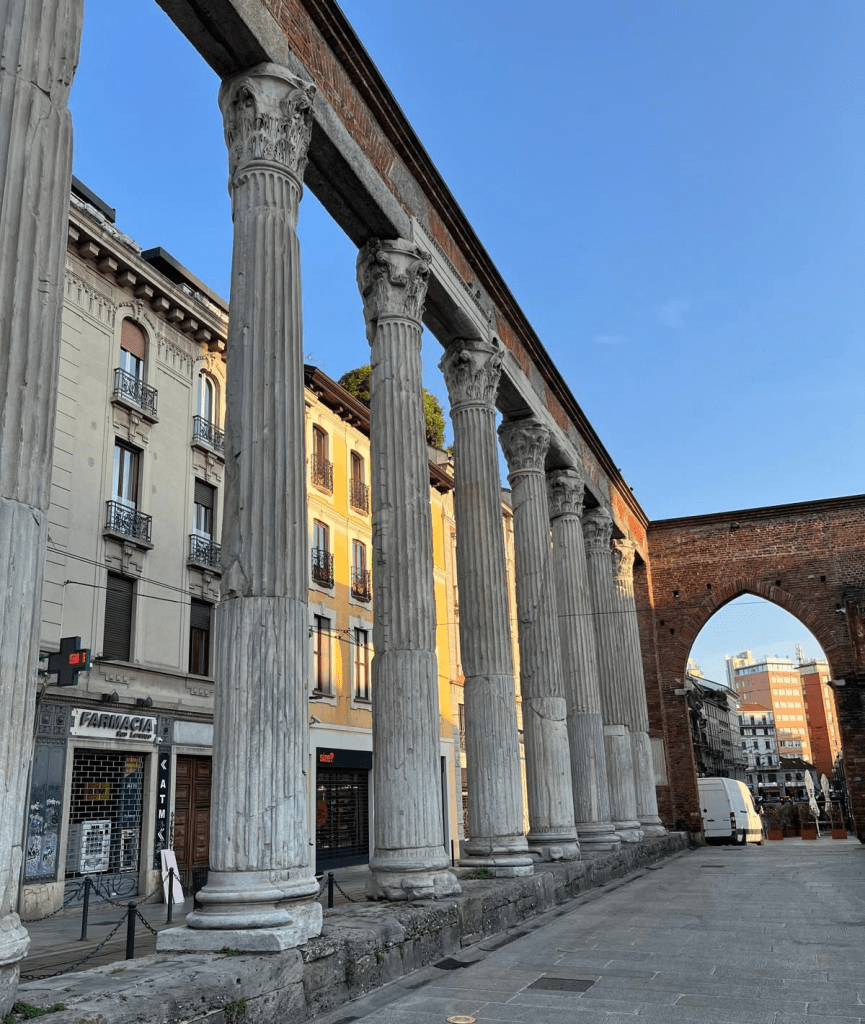

More than 8 million tourists visit Milan every year, attracted mainly by its art, its culture, its fashion and design, the Duomo and its other churches, or even a football ‘cathedral’ like the San Siro Stadium. Not many of these visitors, though, are aware that Milan was once the heart of Roman civilization: it was in fact the capital of the Roman Western Empire for more than a century, from 286 AD until 402. Ancient Romans called it Mediolanum, the ‘central place’ in the Po Valley (or maybe ‘half woolen’ from a boar that was its ancient symbol). The most remarkable legacy of the Imperial city are the Colonne di San Lorenzo in front of the Basilica di San Lorenzo Maggiore (Saint Lawrence Church), one of the oldest churches of Milan. We are near the medieval Ticinese Gate (Porta Ticinese), the southern exit toward the canals Navigli Grande and Pavese and the city of Pavia.

The sixteen marble Corinthian columns were brought there in 4th century, probably after they were removed from a 2nd century pagan temple located in the area of today’s Piazza Santa Maria Beltrade, to form an atrium in front of the ancient basilica. Remains of a bathhouse and of an amphitheatre have been found nearby. The columns are in Musso marble (a greyish-white, hard and compact marble from the quarries near Como), they are seven and a half meters high, with Corinthian capitals that support the entablature.

In reality there are 17 columns, in fact on the top of the arch at the center there is a miniature column with the cross on top.

The columns have an emotional meaning for the Milanese, because they bear witness to the history of ancient Mediolanum having survived the destructions of the Goths and Barbarossa and the bombings of the Second World War.

Located just a few hundred metres from the heart of the city, they are also a meeting place for the nightlife in the bars and restaurants that dot the area.

The capitals of the columns were taken from two different buildings as you can see from the different style and size. In the Middle Ages, between the 11th and 12th centuries, a thickness was added above the lower capitals to level them with the others.

The colonnade has not always been in that position. When the church was rebuilt after various tragedies (fire, collapse of the large chapel), they were placed on the edge of the square in front of the church. In the past the whole church was surrounded by old houses abutting to the façade that were demolished in 1935 to allow renovation work on the church. The Basilica was damaged during the Second World War when the surrounding district was bombed.

In 1937 the square with the Costantinus statue was created at the front. The bronze statue is a modern copy of the antique original preserved at the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano, in Rome. The new square was subsequently occupied by tram tracks, which in the 1990s were moved beyond the Columns. A park was developed at the backside of the church that is officially called Parco Papa Giovanni Paolo II, but is locally called Parco delle Basiliche.

South of the columns, one of the medieval gates still has some Roman marble decoration in place. In the 16th century, in preparations for a celebratory entrance into Milan of the monarch King Phillip II of Spain, it was proposed to raze the colonnade to widen the route but Ferrante Gonzaga, governor of the Duchy of Milan, declined the suggestion.

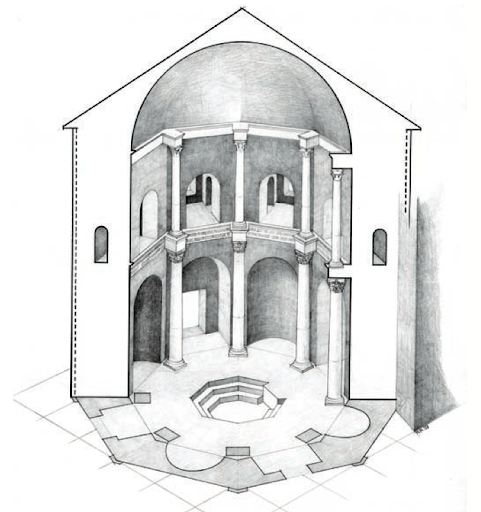

After you admired the columns, visit the Basilica: the total lack of epigraphic or literary sources made the dating and attribution of San Lorenzo, believed to be an imperial mausoleum and/or a martyr church, an unsolved problem for a long time. Dated between the end of the 4th and the middle of the 5th century AD, it was probably built for an Emperor, maybe Theodosius, who died in Milan in 395 AD.

Don’t miss the Chapel of Sant’Aquilino (V century AD), that is connected to the ancient Basilica by a forceps-shaped atrium. The portal has a marble frieze from the I century AD sculpted with Dionysian scenes, chariot races and refined ornamental motifs.

Of the ancient mosaic cycle in the atrium, only a few fragments remain today with the representation of the Patriarchs of the ancient tribes of Israel and a passage relating to the episode of Tamar.

In the octagonal hall, the only surviving mosaics refer to two precious apse basins depicting Christ the magister among the apostles and Christ-Helios with the solar chariot. Very interesting is the choice to use Christian and pagan iconography

The chapel of Sant’Aquilino could have been an imperial mausoleum. It contains a monumental sarcophagus in Proconnesian marble, known as that of Galla Placidia, the Byzantine princess who died in 415 AD. In reality the sarcophagus dates back to the 3rd century AD and was reworked in the VI century to accommodate a new Christian recipient.

As in Pantheon, in Rome, the anonymous architect working in Sant’Aquilino carefully studied the path of the sun over the building in order to place the windows in a position that on Christmas Day allows the sun’s rays to enter from the east, in correspondence with the quadriga mosaic, and then head towards the floor, indicating, according to tradition, the privileged burial place of the emperor. This play of lights is still visible every December 25th. In ancient Rome, Mithra, the god of the invincible sun (Sol invictus), was celebrated on December 25th. When emperor Constantine in 330 AD converted to Christianity, December 25th was celebrated no longer as “Natalis solis” but as “Natalis Christi”.

Through a tiny passage underground you can see traces of the foundation plateaus of a public building dating back to the end of the first century AD.

History and Roman Legacy

Mediolanum was originally settled by the Celtic tribe of the Insubres around 590 BC. Its original name meant ‘in the middle of the plain’, there are around sixty such toponyms in the continental Celtic world. The Romans defeated the Gauls at Clastidium (Casteggio) and then besieged and conquered the city, latinizing its name in Mediolanum.

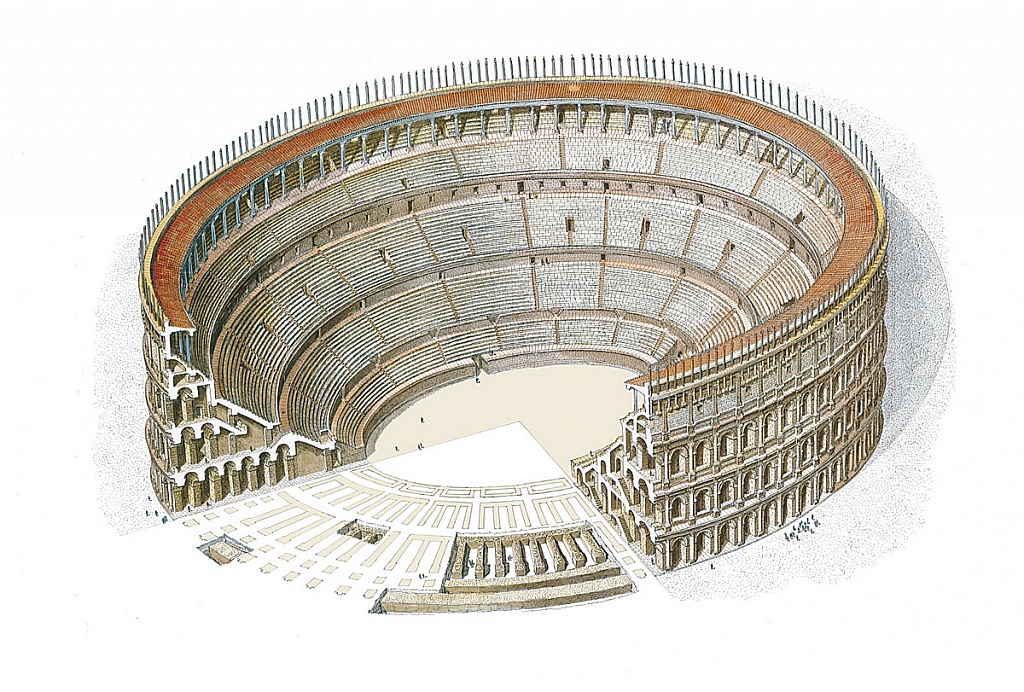

In 49 BC Milan was transformed into a municipium and trade and craftsmanship flourished. Large stone walls encircled the entire city to protect it against barbarians and during the time of Augustus the city became famous for its amphitheatre that could house more than 20.000 spectators.

Mediolanum became the capital of the Western Empire in 286 AD. Since the Roman Empire had become too extensive to manage and to defend from Barbarian tribes, Emperor Diocletian divided the imperial territories into the Eastern and Western empires with two Emperors and two vice emperors (the so called tetrarchy, a power of four people). Two coexisting emperors called Augustus and two vice emperors called Caesars managed the empire from four different capitals. Maximian (also called the Erculean), named by Diocletian to guide the Western Empire, chose Mediolanum as the main seat of his court for its strategic position, near the main mountain passes and at the heart of the Po Valley.

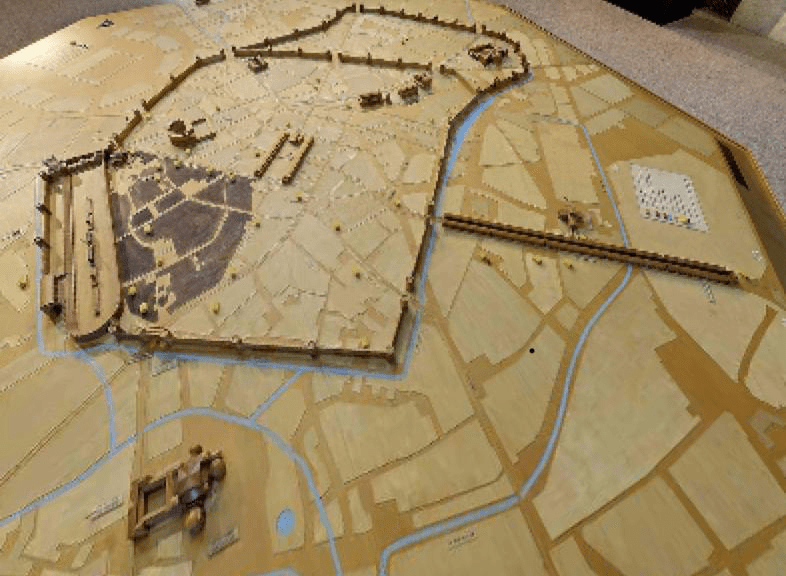

Mediolanum was already one of the finest cities of the Empire (“wealthy and exquisite city”, in the words of poet Ausonius) with a theatre, an arena, a forum with its temples, protected by mighty walls.

Emperor Maximian restored and enlarged many public buildings and built a new circus, his imperial palace, a horreum (a warehouse for foodstuffs) and the imposing baths that would take his name: the Herculean baths.

A few years later, in 313 AD, Constantine, the first Emperor to convert to Christianity, celebrated his daughter Flavia Julia Constantia marriage to his co-emperor Licinius in Mediolanum. In the same year he signed the Edictum Mediolanense that guaranteed freedom of worship to all the Empire’s inhabitants.

Ancient Rome Itinerary

A couple of tips before we start our ‘tour’: the Roman-era heritage of Mediolanum is still visible in several churches that have been renovated and transformed over centuries. Besides the Columns of San Lorenzo, a real treasure can be found in the Basilica of St. Ambrose (patron saint of Milan), which dates back to 386 AD, around the time the Romans embraced Christianity. The basilica itself was rebuilt in the Romanesque style later in the 12th century, but its wonderful Chapel of Saint Vittore, a golden sky chapel, features a 5th century religious Roman mosaic. Also notice the sarcophagus of Stilicone, a Roman general with German roots.

The church of San Simpliciano and the Basilica of San Nazaro in Brolo are two other examples. They were both founded by bishop Ambrose in the IV century.

In San Simpliciano look for the Sacello dei Martiri dell’Anaunia, a small basilica with a semi-circular apse. San Nazaro is probably the oldest church with a Latin cross plant in Western art.

On Porta Nuova, a 12th century medieval gate in northern Milan, you can find two ancient Roman steles, stone relief sculptures. One of them represents members of the family of cloth merchant Caio Vettio. Roman walls A Roman itinerary may start in via San Giovanni sul Muro, not far from Cairoli metro station (red line), where ancient walls near Porta Vercellina (49 a.C.). are still visible.

The Porta, situated where Santa Maria della Porta church now stands, marked the beginning of the road to the Gaul that connected Mediolanum to Taurinorum (Turin) and Vercellae (Vercelli). The city in today Piedmont gave its name to the Porta that was demolished during Milan siege in 1162.

Archaeological museum – In Corso Magenta 15 a ‘must see’ is the Archaeological Museum with its special section dedicated to the Roman period (there are also Greek, Etruscan and early medieval manufacts) and the only raised remains of Mediolanum when it was capital of the Empire. In the atrium a large wooden plastic shows the monuments and the topography of the city from I to III-IV century AD.

The mosaics in the basement come from the ‘innumerae cultaeque domus’, the many stately houses in Mediolanum described by Ausonio.

The showpiece is the Coppa Trivulzio, named in honour of the noble Milanese family that owned it before it was bought in 1935 thanks to a public fundraising. It is a stunning blown-glass, fretwork-crafted masterpiece, dating back to the late Roman Empire.

Other interesting pieces are the statue of Hercules at rest (IV century AD) that ornated the Herculean Baths, the giant Head of Jupiter and the silver plate Patera di Parabiago showing the myth of Cibele and Attis (it is probably connected to the attempt of intellectual elites to restore pagan traditions in the second half of IV century AD).

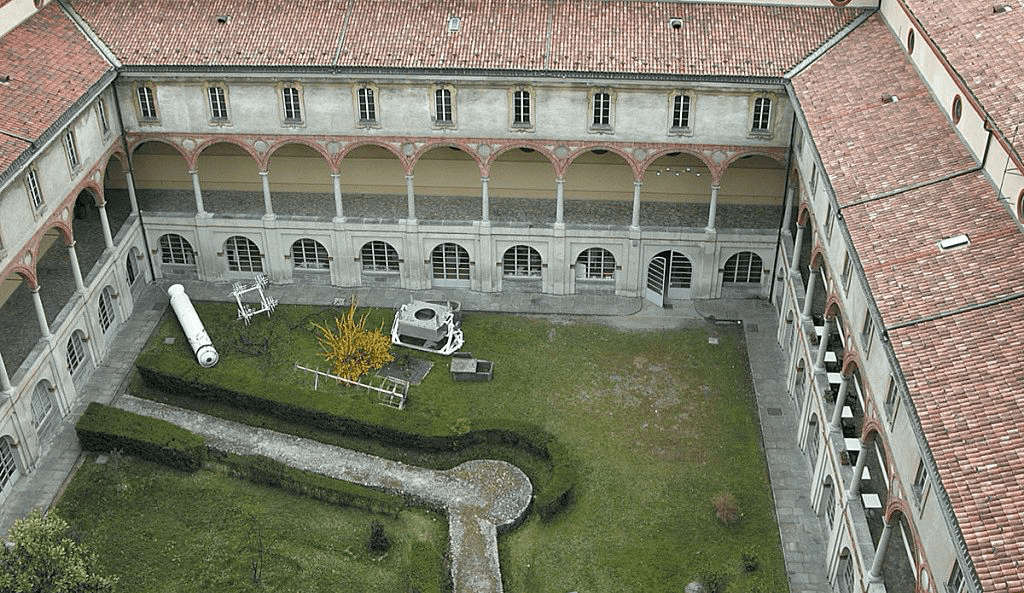

In the cloister a collection of epigraphs offers an interesting overview of mediolanensis society.

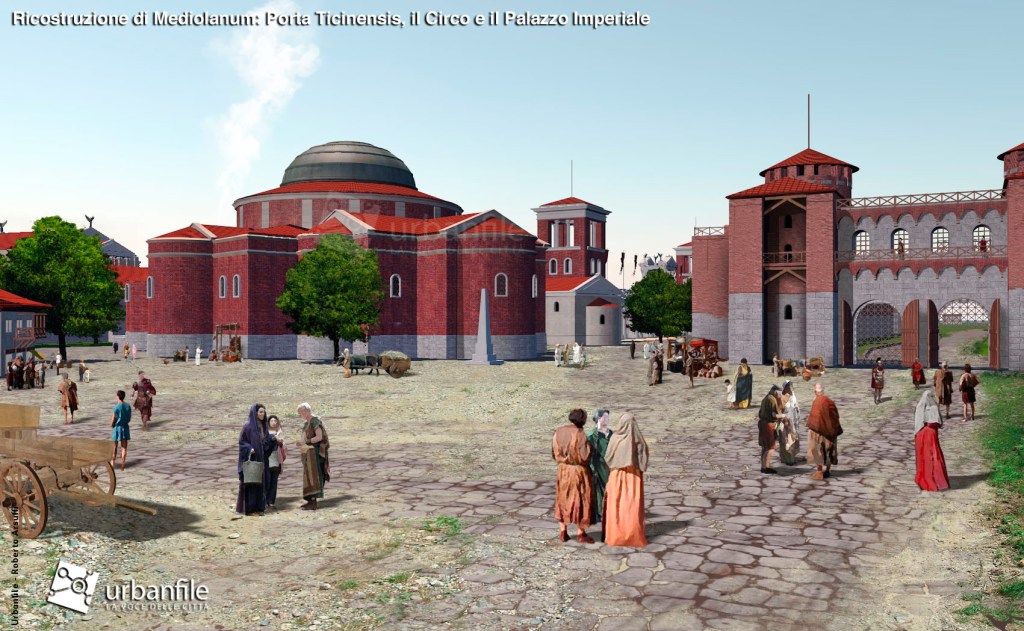

In the outer patio there are the remains of the circus with its tower that has been transformed into a bell tower (it takes its name from bishop Ansperto). Erected between the end of 3rd century and the beginning of 4th century AD, at the request of the emperor Maximianus Herculius, it represents the best preserved part of the Mediolanum’s roman racecourse .

The structure was one of the two towers of the carceres, the starting gates from which the chariots departed. The circus was 470 meters long and 85 meters wide, definitely too big for a city of 50.000 inhabitants but it projected a sense of power for the Empire. The circus was gradually demolished by the Milanese and finally destroyed by Barbarossa.

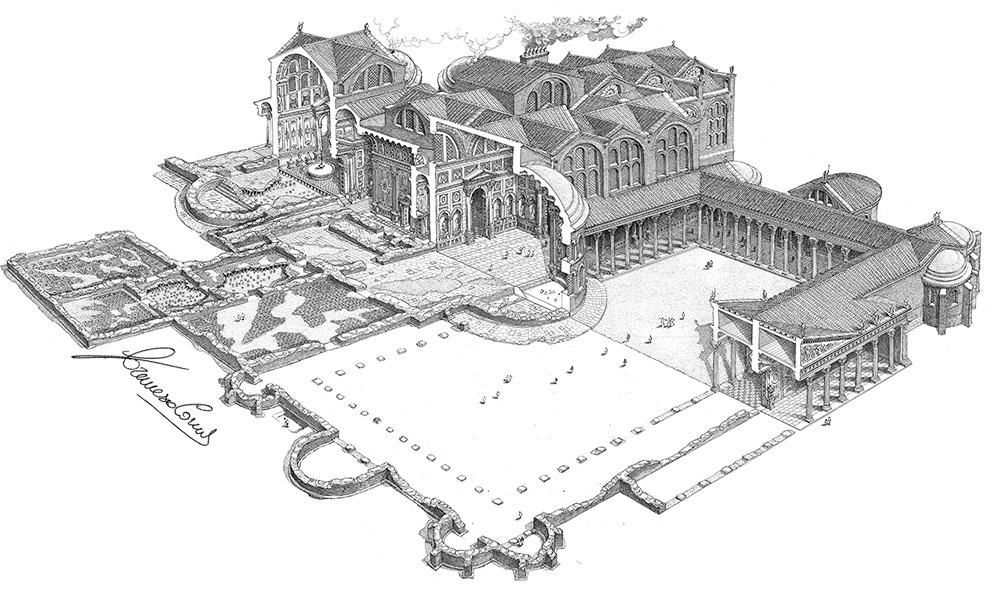

At the lower floor of the tower, used by the medieval convent (there are frescoes), you can access from the museum, while the upper part is only accessible with a qualified guide. The museum is in the former monastery of San Maurizio and since you are there you can’t miss a visit to the church of San Maurizio next door with its ‘Milan Sistine Chapel’, even if it has nothing to do with Ancient Rome. The Imperial Palace In via Brisa there are the remains of the palace of Emperor Maximian (250-310 AD), brought to light in 1951.

The palatium, built in 287 AD, was the residence of the Emperor and his court and occupied the area between today Corso Magenta, Via Santa Maria alla Porta, Via Torino and Via Circo.

The area clearly visible from above belonged to a large representative sector. In addition to the foundations, some sections of the elevation are also preserved, up to 1.40 meters in height.

Notice the central room, circular in shape with a diameter of 20.70 metres, that was colonnaded and other rooms converged on it. The most imposing one was made up of a large apsidal reception hall: on the two east and to the west there were two symmetrical rooms (2-3), with a curvilinear apse in the center and two rectangular apses on the sides (alcovae).

On the western side of the peristyle there was a second nucleus with an apsidal room in the center, but smaller in size than the large room to the north, flanked by two mirrored rooms (alcovae) and another space that was a triclinium or maybe had resting function (cubicula). All rooms had to be heated, with the exception of the circular peristyle. Domus in via Amedei In the Seventies, some rooms of a rich domus were brought to light in via Olmetto-vicolo San Fermo, decorated with flooring, some of which are now in a museum in an underground room accessible by request from via Amedei 4, under Palazzo Majnoni d’Intignano.

A house dating back to the end of the 1st century BC has been identified with rooms decorated with black and white mosaics, two fragments of which are exhibited in the underground room: one of them has a precious border representing the walls and towers of a city. In the same neighbourhood, various environments referable to this period have been highlighted. They could belong to a single building or to a single insula (neighborhood of houses). Domus in via Broletto Between 2002 and 2003, a housing complex was brought to light beneath Palazzo Carmagnola, in an area that in ancient times was near the walls

The house, oriented according to the route of the cardo maximus (north-east/south-west), was built in the Augustan age and it had at least five rooms with decorated floors and walls: traces of the floor in one room show a layer of lime and white stone chips, smoothed and embellished with black tiles arranged to form. From the windows in the courtyard of Palazzo Carmagnola the museum rooms in the basement are visible. You can observe the presence of a larger room, dating back to the 1st century AD, with a floor in black and white tiles. Next to it is a second room, towards the south, heated with a hypocaust, of which the pilae are still preserved. Baptistery under Milan Duomo

Don’t miss the archeological area below the famous Milan Duomo, with the remains of some buildings of worship dating back to the period between the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, demolished to make way for the construction of the new Cathedral. You can find the large octagonal baptismal pool of the Baptistery of San Giovanni alle Fonti, built in 378, inside which Saint Ambrose baptised Augustine in 387.

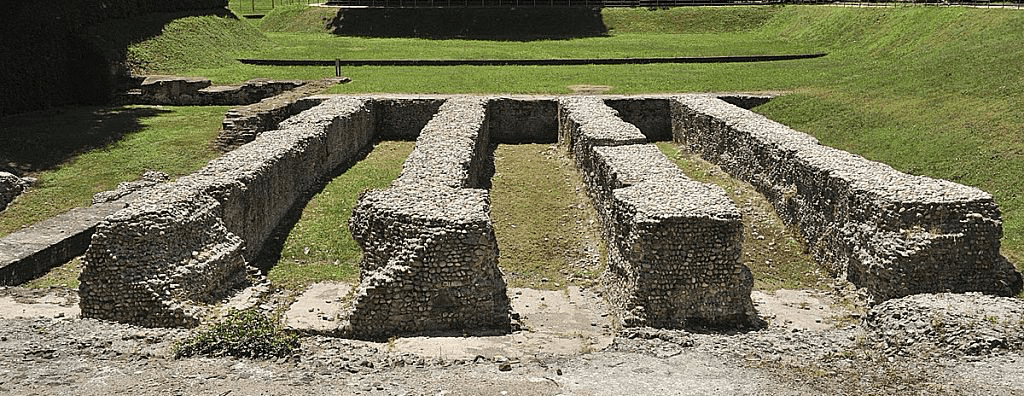

Next to the Baptistery was the Summer Basilica of Santa Tecla (IV century AD) of which portions of the apse are still visible. Some tombs of prominent people and traces of an ancient thee-apse hall have also emerged, most likely intended for funerary purposes. Horreum, the Roman warehouse In late ancient times, Mediolanum undoubtedly possessed a large horreum, built not far from the city walls surrounded by the moat which facilitated the supply of goods.

Built near the road axis heading towards the ancient Novum Comum (Como), the warehouse had the main purpose of supporting the troops stationed in the city for the defense of the empire’s borders.

The structure, still partly visible in via Bossi, 4, was 18 meters wide and 68 meters long. Internally it was divided into four naves by three rows of sixteen pillars, the central ones of which were larger; the internal facades were punctuated at regular distances by the presence of brick semi-pillars (pilasters). Roman theatre

Between Piazza Affari and Via San Vittore al Teatro there are the remains of an ancient theatre, the oldest public building in the city that dates back to the 1st century BC, during Augustus Empire: it could host 15.000-20.000 spectators.

The theatre was located in the heart of the imperial city. It was the first large building built in Mediolanum as part of a broader construction work of important masonry structures. The theater maintained its original function until the 4th or 5th century, when the edicts of Theodosius and the progressive conquest of power by the Church began to hinder theatrical performances and games. The last show of which we have news is the proclamation as consul, inside the theatre, of Manlius Theodore, which took place in 399. It is possible to book a visit at Palazzo Turati at the local Chamber of Commerce that allows you to see the foundations of the cavea , the space in which Roman spectators, sitting on steps arranged in a semicircle, observed the actors move on the stage. A multimedia path allows visitors to smell essences and odors from the period of imperial Rome, from the scent of rose to saffron, from sweet wine to human and animal smell. Lights and shadows escort you on the transparent walkway that highlights the remains of the steps of the theatre, with a background of sounds, voices and noises. Visitors are also guided by the voice of italian actor Giorgio Albertazzi, who recites in Latin lines from the prologue of a comedy by Plautus, the Càsina.

The theatre probably remained in use until the 4th century and in the medieval age it became a meeting place for the People’s Assembly in the municipal era. According to scholars if the theater had not been destroyed, most likely by Federico Barbarossa following the siege of 1162, the auditorium of the theater would have remained almost intact until today. The Imperial Mausoleum

Remains of the sumptuous Imperial Mausoleum of the Valentiniani family can be seen in the Church of San Vittore in Corpo, in Via San Vittore. The octagonal enclosure, internally 132 meters long and 100 meters wide, had sides 42/44 meters long and was equipped with semicircular towers at the top. The northwestern section of the wall, the only one preserved above ground, had niches flanked by semi-columns. The monumental entrance was located to the south-east and flanked by two towers.

Part of the octagonal enclosure is still visible in the cloister of the Science and Technology Museum (Via San Vittore, 21). Domus in via Morigi

In the atrium of a house in Via Morigi 2 you can admire from the street the remains of a floor in beaten mortar with marble inserts from an elegant domus of the I century BC, one of the oldest of Mediolanum. It was part of an ancient quarter that was then incorporated in the Imperial Palace. The refined floor has a layer of lime and pressed stone flakes (cement), decorated on the surface with inserts of colored stones, framed along the edges by a frame with black and white tiles. In Via Morigi, 13 there is a room heated with a hypocaust system, with the support of pilae.

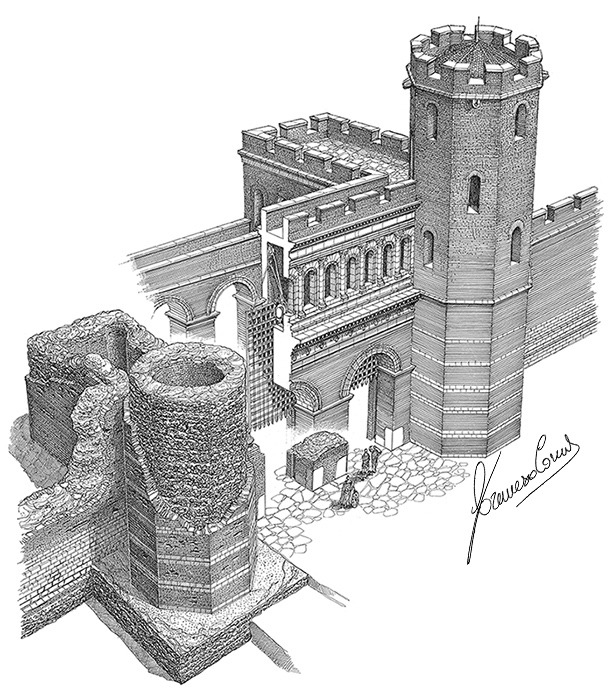

In Largo Carrobbio you can admire the Tower of the Muslims, the only surviving remnant of the Porta Ticinensis (Porta Ticinese, so called because it was in the direction of Ticinum, Pavia) of the first century BC. It is visible from the parking lot of Ariston Hotel from the outside and in the restaurant Pane e Vino from the inside.

Nested at the junction with Via Medici, Porta Ticinensis reunited “the two sections of the Augustan and Maximian walls that had separated at the Vercellina gate to embrace the Circus”. At the time the Porta had a double fornix (opening) flanked by two massive towers of eight sides each.

The Amphitheatre – In via De Amicis 13 you can see the remains of the Amphitheatre, one of the largest in northern Italy that dates back to the first century AD. outside the city walls, in the Porta Ticinensis area.

The amphitheatre, 155 meters long and 125 meters wide with an external wall 38 meters high, could host up to 20.000 people and Ausonio called it Voluptas populi,’ joy of the people’.

The arena hosted fights between men and between animals, simulations of hunting trips (venationes) and even naval battles in the artificially flooded arena. The enthusiasm and fanaticism of the crowds often led to serious disorders: also for this reason amphitheatres were built outside or on the edge of urban centres. In Mediolanum it was near the ancient Porta Ticinensis, in the area of Via Arena. It is open Tuesday to Saturday from 9.30 to 16.30: the visit is free. In the nearby Antiquarium there are interesting finds like the funerary plaque for gladiator Urbicus, who died when he was only 22 years old. In Piazza San Sepolcro there was the Roman Forum, it is possible to admire a part of the original pavement in the basement of the Ambrosiana Pinacoteca in Milan (see ‘Fun fact’ section).

Herculean baths

Crossing the passage between Corso Vittorio Emanuele II and Corso Europa, in Largo Corsia dei Servi, the remains of the walls of the Herculean baths built under Emperor Maximian are visible, relocated following their discovery at -3.50 meters from the current road surface.

The baths, like many buildings in Milan, rested on wooden piles. They occupied an area of approximately 14,500 m2: the area chosen corresponded to the north-eastern area near the gate Orientalis.

Two other sections of the foundations are preserved in the small garden next to the church of San Vito al Pasquirolo and a part of the tepidarium is under a building in Corso Europa.

Finally, since you’re in Millan we suggest a visit that is not strictly ‘Roman’ but that offers a surprising glimpse in the Etruscan civilization, strictly connected with that of the Eternal City. In an historic Milanese Palazzo across from the gardens of Via Palestro, you can find the Museum of Art of the Fondazione Luigi Rovati, at no. 52 Corso Venezia.

The Museum houses a rich collection of Etruscan ceramic, bronze and gold objects. The exhibition route unfolds from the wonderful Hypogeum floor (Level -1) to the Piano Nobile (Level 1), in a journey that takes visitors from past to present – with over 200 artefacts of the museum’s Etruscan collection exhibited alongside modern and contemporary artworks.

Fun Fact – Milan Forum and Augustus’ rage

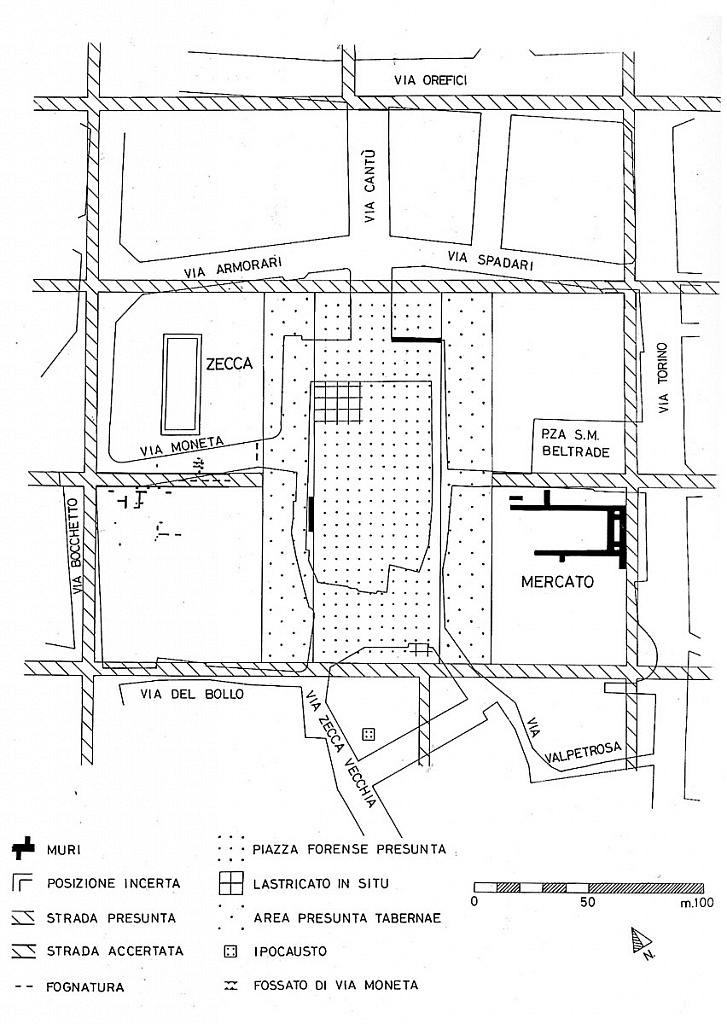

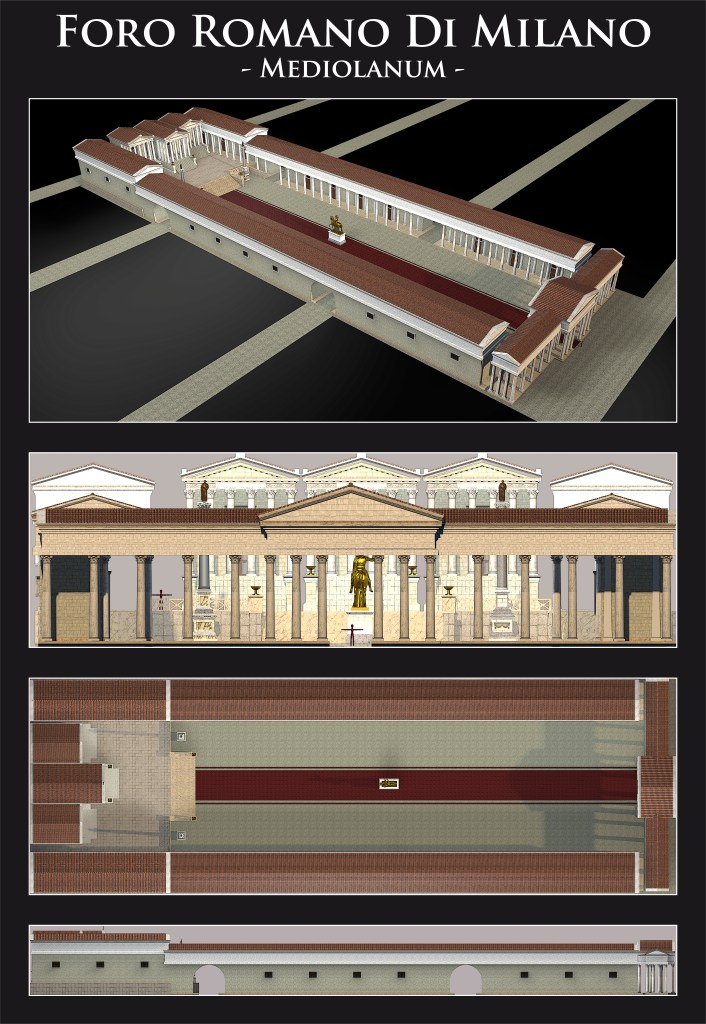

The forum of ancient Mediolanum was located at the intersection of the main road axes, in the area now occupied by the Ambrosiana Library and Art Gallery and the church of San Sepolcro, the Holy Sepulchre, on the square that is considered the birthplace of Fascism since Benito Mussolini the rally in 1919 in which he founded the ‘Fasci di combattimento’.

The forum, built under Augustus in the 1st century AD, was a rectangular area of 55 x 160 meters wide, similar to those of Brescia and Pompeii and corresponding to the typology described by the architect Vitruvius.

Underneath the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, the Ambrosiana Library it is possible to see part of the pavement of the original Forum, the heart of Mediolanum that hosted the most important administrative and religious activities. It is made of large rectangular slabs of red Verona marble with irregular sizes because they still have the original shape, which once accompanied the profile of the buildings adjacent to them. Other fragments of the flooring are in the crypt underneath the church of San Sepolcro accessible from the backyard of the Library.

Suetonius and Plutarch recall a bronze statue in the forum of Lucius Junius Brutus, the first Roman consul who expelled the kings from Rome and who was the ancestor of Marcus Junius Brutus, the most famous of Caesar assassins.

Mediolanum did not forgive Caesar for his royal ambitions and did not support, at least initially, the principatus of Augustus, maintaining its republican sympathies even after the decisive battle of Philippi where Brutus committed suicide. It was reported that Augustus flew into a rage when he saw the statue intact in the Forum but then, calming down, he reassured the dismayed Milanese and praised them for their loyalty to the memory of their benefactor, who had been very popular when he was governor of Cisalpine Gaul, the region of Northern Italy with Mediolanum, from 47 BC. At that time Brutus had even promoted a revolt in the region against the faction of the optimates, aristocrats who supported the Senate.

Useful informations for Milan

Basilica di San Lorenzo Corso di Porta Ticinese, 35 Opening times – From Monday to Saturday from 8 am to 6.30 pm, on Sunday from 9 am to 7 pm. For the chapel of Saint Aquilino a ticket is required. www.sanlorenzomaggiore.com

Museo archeologico di Milano Corso Magenta, 15 – from Monday to Sunday, from 10 am to 5,30 pm. https://www.museoarcheologicomilano.it

Our tabernae, where to eat

Pasta d’autore – Very close to San Lorenzo columns, Pasta, pizza cooked in a wood oven and regional wine.

Corso di Porta Ticinese, 16 (+390235953304)

Leave a comment